A Few Essential Updates

By Norbert Gleicher, MD, Medical Director and Chief Scientist, at The Center for Human Reproduction in New York City. He can be contacted directly at ngleicher@thechr.com.

This article was originally published in The Reproductive Times and has been updated to reflect recent regulatory and policy developments.

How Confident Is Society Still in the Scientific Enterprise?

By Norbert Gleicher, MD, Medical Director and Chief Scientist, at The Center for Human Reproduction in New York City. He can be contacted through the editorial office of The Reproductive Times or directly at either ngleicher@thechr.com or ngleicher@rockefeller.edu

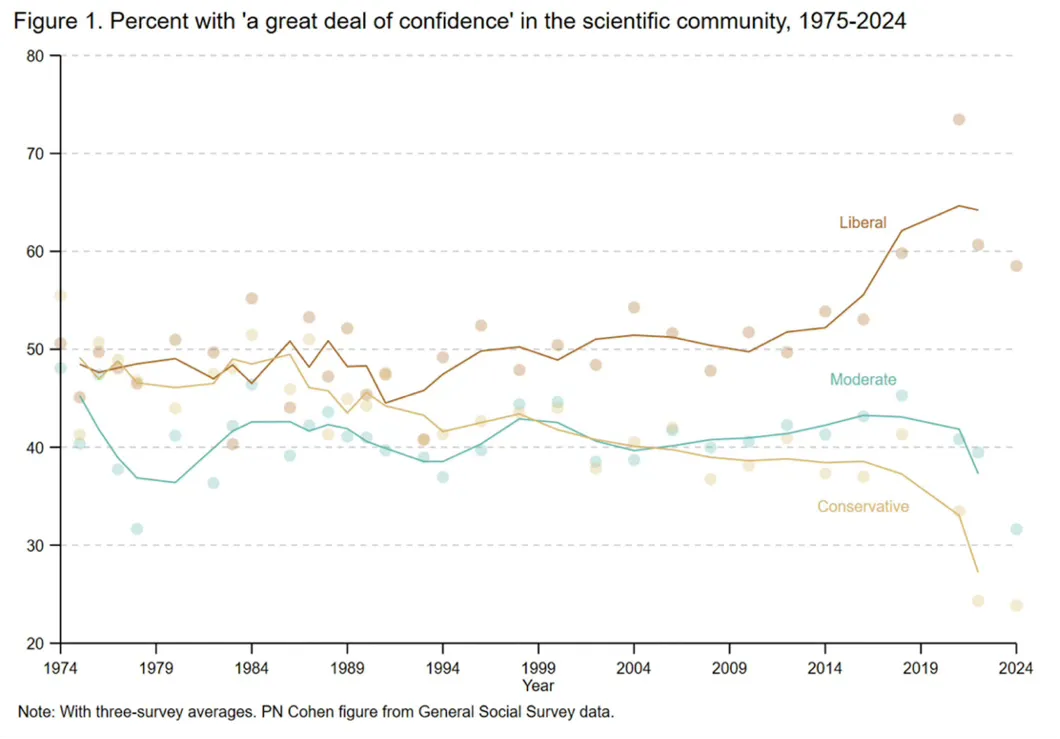

The business of medicine, of course, almost more than any other sector of the economy, is totally dependent on the confidence of society in science. For that reason, one of the weekly TGIF columns by Nellie Bowles in The Free Press, which the CHR’s Medical Director and Chief Scientist, Norbert Gleicher, MD, considers his favorite weekly media column, attracted his special attention. Bowles, in the column, reprinted a figure (Figure 1) from a recent (preprint) paper by a sociologist from the University of Maryland, demonstrating widely different perceptions among Liberals and Conservatives about their confidence in the scientific enterprise. Though she claimed “to need a microscope to spot the trends,” Gleicher found the trend curves fascinating and decided to go to the source paper, which disappointed him in the rather simplistic and obviously politically biased interpretation of observed trends by the author. He therefore decided to initiate an experiment on his own: recognizing pretty obvious time points for changes in opinions among Liberals, Moderates, and Conservatives in Figure 1, he queried ChatGPT about societal developments that could have led to these changes. And ChatGPT’s responses were beyond interesting and informative.

How much confidence society still has these days in the scientific enterprise is—at least in science circles and the media—a not infrequently discussed question. It, of course, is also a crucially essential question for medicine, which supposedly is more and more built on science. The consensus in answering these questions has, however, increasingly been going in the wrong direction, with society seemingly progressively losing confidence, a widely attributed reason being the poor performance of government and its science advisors during the COVID pandemic.

But a recent preprint by Philip N. Cohen, PhD, a sociology professor at the University of Maryland,¹ and brought to our attention by Nellie Bowles in one of her brilliant weekly TGIF columns in The Free Press,² allows for somewhat different inferences.

They are best explained with a short introduction to the subject: building on two earlier studies, Cohen updated data to 2024 in determining how the U.S. perceives societal confidence in science based on the political identity of individual citizens. The study question, in other words, was how Liberals, Moderates, and Conservatives from the mid-1970s to now have perceived the standing of science in society. As this study basically only updated two prior studies, it was already known that differences between these three subpopulations existed. For that same reason, we also do not address the study design (and its weaknesses), assuming real-world experience from a very large population cohort.

Figure 1 below summarizes the data for the whole study period, including the materials for two earlier papers.

As this figure demonstrates, confidence in science was never really great; it, however, also was never—at least until roughly 2004–2009—as bad as it often was made out to be. But what really captured our attention and is fascinating is how political persuasion over time changed regarding how society has been feeling about science. And the most radical changes started already several years before COVID changed all of our lives. Society’s declining trust in science, therefore, has—likely—only very little to do with what happened during COVID.

Truly amazingly—if we are to believe this figure—between the mid-1970s and the early 1990s, Conservatives and Liberals almost shared identical opinions about the credibility of science, with roughly half of both groups having a great deal of confidence in science. The outliers in those years were the Moderates, who, with mild variability, have not much changed in their relative skepticism and on average have trusted science at only about 40% to this day.

But in the early 1990s, something interesting happened to Conservatives: their trust in science started a steady decline, which has not stopped to this day and indeed accelerated around 2015 and ultimately became a waterfall with the COVID pandemic, with trust in science expressed by just a smidgen above 25% of Conservatives after the pandemic ended.

In contrast, around 2010 (a very important date for reproductive medicine and especially IVF, to which we will return), Liberals suddenly started believing in science, increasing the percentage from approximately 50% to almost 65% of individuals who strongly trusted science, even though Nellie Bowles still felt “she needed a microscope to spot a trend.”

Cohen, the author of the paper, in turn, looked at the results—as one would expect from a sociologist—only “politically” by arguing that the observed growing division between Liberals and Conservatives “undermined the notion of modernity as an era of increasing trust in science (so far we agree); yet it is not part of a general mistrust of science, because it is not apparent among those with less conservative views.” He then further argued (and this is where we depart from his interpretation) that “as the divide widens, it may become easier for right-wing political leaders to use mistrust of science to mobilize conservative skeptics for partisan ends” (as if Liberals don’t use inherent liberal opinions to their partisan ends). Why must every sociologist automatically always be on the political left?

So we decided to consult ChatGPT as to what societal developments could have influenced these quite radical changes in the opinions of Liberals and Conservatives (without affecting Moderates), as Figure 1 very clearly demonstrates.

We first wanted to understand what, in the early 1990s, quite suddenly, might have adversely affected the credibility of science (at least among Conservatives). And here is what ChatGPT told us:

Several overlapping developments in the late 1980s to early 1990s weakened public confidence in science—not because science suddenly became worse, but because its authority, incentives, and visibility changed. Among those:

(i) The entanglement of science and industry became obvious, undermining the idea of science as a disinterested truth seeker.

(ii) The replication crisis began quietly, with the “publish or perish” culture intensifying, journals favoring novel and positive results, and statistics being misused through so-called p-hacking and selective reporting.

(iii) With the end of the Cold War (1989–1991), the role of science in society changed. BEFORE, the importance of science in national defense and the space race offered unquestioned prestige. AFTER, science had to justify funding through policy relevance, and research became tied to political agendas such as the environment, health, and economics, looking like just another political weapon.

(iv) The spread of so-called postmodern skepticism in academia, based on claims such as science being a social construct, truth being contingent on power structures, and objectivity being illusory, eroded trust in scientific authority.

(v) Media transformation and early internet effects presented conflicting expert opinions as equal, exaggerated uncertainty, and reported preliminary findings as facts, all making science appear inconsistent and unreliable.

(vi) Public scientific failures became visible, such as the cold fusion claim collapsing in 1989, dietary advice reversals, medical treatment reversals (for example, postmenopausal hormone treatments), disease screening practices, etc.

(vii) Society shifted from “elite trust” to “institutional skepticism,” and the early 1990s marked a transition with declining trust in institutions (government, media, universities), a rise in individual skepticism (“do your own research,” as we are doing here), and increasing questioning of authority. In other words, science lost its protected status as an unquestioned institution.

All of these explanations very well and credibly explain why society in the early 1990s would have undergone quite a dramatic change in its perception of science. These explanations, however, only further ask for answers regarding the increasingly contradictory behavior of Liberals, who—in parallel to Moderates—at least until the end of the 1990s remained more or less unchanged in their attitude toward science, while Conservatives—very clearly reflecting the societal effects pointed out by ChatGPT—logically demonstrated clear declines in their appreciation of science.

In other words, it was the Conservative part of society (in contrast to Moderates and Liberals) that expressed progressive behavior changes in response to new societal realities, while Moderates and Liberals basically ignored all of these societal changes, i.e., “put their heads in the sand.” Weren’t Conservatives, therefore—in contrast to how Cohen interpreted them in his paper—the real progressives during this time period?

Now that ChatGPT gave us a very logical understanding of what the societal changes were in the late 1990s that separated Conservatives from Moderates and Liberals, let us see what ChatGPT told us happened starting around roughly 2010, which led to a precipitous parting of ways between Liberals and Conservatives by approximately 2015, with Liberals suddenly becoming true believers in science and Conservatives basically losing almost all trust (see again Figure 1). We did this in two separate queries: in the first, we asked ChatGPT what societal developments around 2010 could have reduced trust in science, and in a second query, we asked what societal developments around 2010 could have enhanced trust in science—and ChatGPT, again, did not disappoint.

In response to the first query, ChatGPT offered the following answers: Around 2010, several overlapping societal and technological shifts in the U.S. converged in ways that (at least in Conservatives) eroded trust in science, even though scientific output was growing.

(i) The tipping point being 2008-2012, social media became a primary information source. Algorithms rewarded emotion, outrage, and novelty, not accuracy. Scientific uncertainty (normal in science) was reframed as weakness or dishonesty. Fringe and contrarian voices gained the same visibility as credentialed experts.

(ii) The politicization of scientific issues intensified, and several scientific topics became “identity-linked:” Climate change became a partisan marker rather than a technical question. Especially after the 2009 H1N1 flu season, vaccines became entangled with libertarian and parental-rights rhetoric. Evolution vs. creationism resurfaced in education debates, to later be followed by GMOs and fracking. As a consequence, trust in science increasingly depended on political affiliation rather than evidence.

(iii) A decline in gatekeeping by traditional media: BEFORE ~2010, science reporting passed through editors and specialist journalists; AFTER ~2010, newsrooms shrank dramatically, science desks were cut, and click-driven headlines oversimplified or sensationalized findings. Here are two examples: “One study says …” in place of reporting; treating preliminary or non-replicated findings as settled facts, with the effect being that the public saw science as inconsistent, flip-flopping, or hype-driven.

(iv) The replication crisis became public, with around 2010-2012, researchers openly (for the first time) acknowledging problems in psychology, biomedical sciences, nutrition research, and social sciences. Key issues that evolved were non-reproducible results, P-hacking, publication biases, and industry-funded studies, with the effect being that legitimate self-criticism inside science was interpreted by the public as proof that science was unreliable and corrupt.

(v) Growing distrust of institutions in general after the 2008 financial crisis must also be considered, as it had broad spillover effects after experts (economists and regulators) failed to predict or prevent the crisis. As a consequence credibility of the whole “expert class” suffered, and universities, government agencies, and corporations were seen as interconnected elites. The effect of all of this, in summary, was that scientists were increasingly viewed as part of a distrusted establishment.

(vi) The importance of personal experience rose over “expertise,” leading to a cultural shift toward “my truth,” anecdotal evidence, and influencers over institutions. Examples were: “vaccines harmed my child;” my diet cured me,” and “doctors ignored me,” and with such personal stories spreading faster and feeling more authentic than statistical data. Unsurprisingly, lived experiences, therefore, were often treated as superior to scientific consensus.

(vii) Education gaps in scientific literacy grew significantly, with many Americans lacking an understanding of probability and risk, lacking familiarity with how scientific consensus forms, and lacking awareness that uncertainty is not ignorance. And in addition, science communication often failed to explain uncertainty clearly and overpromised benefits and/or timelines. As a consequence, trust declined.

(viii) A cultural backlash against modernity and globalization, in addition, led to science becoming symbolically associated with global elites, secularism, technocracy, and loss of traditional identities, which fueled anti-intellectualism and suspicion of “experts telling us how to live.”

One cannot have lived through those years without having to conclude that ChatGPT, indeed, successfully summarized the evolving progressively defiant perception of science during those years, mostly expressed by Conservatives, but how would ChatGPT explain the evolving enthusiasm for science among Liberals? And here is the answer, and—once more—it was more than interesting:

It, first of all, correctly recognized the question as a “counter-question” to the prior question and, rather remarkably, addressed it by noting that, while trust in science fragmented after 2010, belief in its values (especially its usefulness) actually rose in many parts of U.S. society, thereby instantly offering explanations for what Figure 1 so obviously demonstrated. And here are nine of these explanations:

(i) Smartphones made science visibly useful in daily, personal, and immediate interaction because, around 2007-2012, smartphones became ubiquitous. Science, therefore, stopped being abstract and became understandable through GPS and satellite navigation, weather forecasting by the hour, medical apps, imaging, and diagnostics, through translation, speech recognition, AI assistants, fitness, sleep, and health tracking, with people suddenly experiencing science a “working” and not as “ideological.” Moreover, those skeptical of scientists now rely constantly on scientific outputs.

(ii) Rapid biomedical and health breakthroughs also contributed because post-2010 advances were highly visible, including CRISPR (2012), cancer immunotherapy, HIV treatments transforming life expectancy, mRNA platform development (pre-COVID), rapid genomic sequencing, prosthetics, bionics, and—yes—fertility technologies. As a consequence, medicine became a powerful demonstration of science’s tangible value.

(iii) After 2010, environmental events made science necessary and no longer optional because of more frequent extreme weather events, such as major droughts, hurricanes, and heat waves, all leading, even among climate skeptics, to rising insurance losses and infrastructure strain. Meteorology, engineering, and disaster science were suddenly seen as essential, and science gained value as a practical survival tool, even when conclusions were contested.

(iv) STEM economically became central. Cultural and economic shifts led to tech companies dominating the economy. STEM degrees were now linked to job security and upward mobility, coding and engineering were now promoted in schools, and “learn to code” became mainstream advice. As a consequence, science was valued as economic power, innovation, and national competitiveness.

(v) Especially after 2010, science was, in tech culture, reframed as “problem-solving,” and no longer as “authority”: less “as experts telling you what to think,” and more as experimentation, iteration, and hacking, which appealed to entrepreneur culture, DIY bio and maker movements, and science projects. In short, science is aligned with American values of pragmatism and innovation.

(vi) Data became a cultural language with explosions in data analytics, dashboards, evidence-based policy language, A/B testing, quantified self-movement, and people increasingly accepting “show me the data,” measurements as legitimacy, with the effect that even skeptics of institutions respected methods associated with science.

(vii) In some spaces (only) science communications improved, as new formats emerged, as Science YouTube (Kurzgesagt, Veritasium), podcasts (Radiolab, Science Vs), public intellectual scientists came on the scene, and better visualizations and storytelling took shape, and science became more accessible, human, and engaging.

(viii) A generational change also came into play as Millennials and Gen Z grew up with technology enabled by science, were more comfortable with complexity and uncertainty, and more likely to value evidence-based reasoning even if skeptical of institutions, so that aggregate belief in science‘s value increased through cohort replacement.

(ix) Even before COVID, smaller crises already showed a pattern of demonstrating science’s power (epidemics, like H1Ni1, Ebola, Zika), environmental disasters, and cybersecurity threats. COVID later dramatically reinforced this, with modeling, testing, and genomics becoming household concepts and science proving itself as indispensable even to critics.

HOW ALL OF THIS RELATES TO REPRODUCTIVE MEDICINE

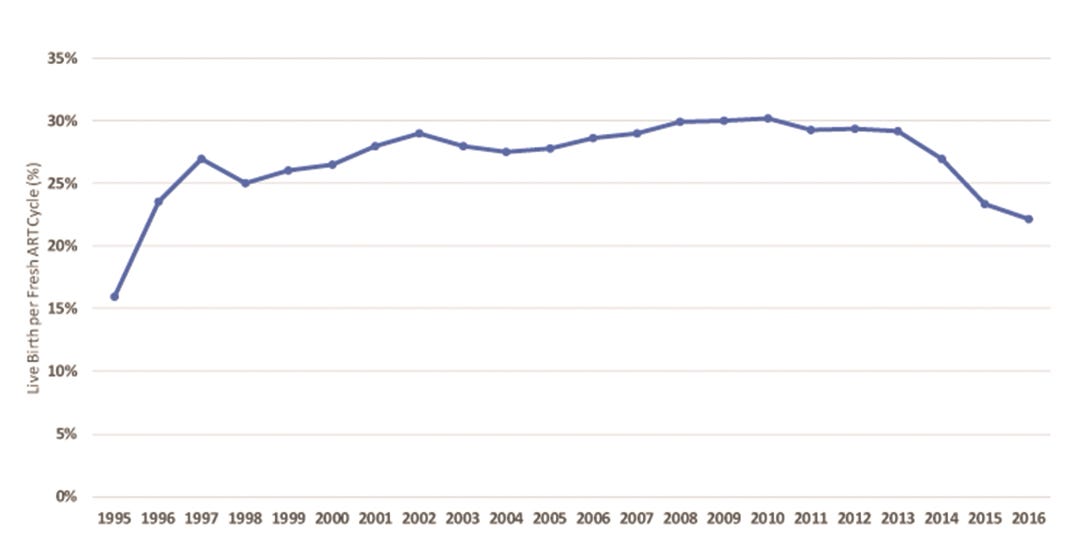

And now a final word about why all of this also has special relevance to reproductive medicine. The reason is that the year 2010 has also special meaning for in vitro fertilization (IVF). Until approximately the year 2010, clinical pregnancy and live birth rates in autologous IVF cycles had steadily improved since the inception of IVF. They plateaued around 2010 and, subsequently, uninterrupted, have been declining to this day, as we first reported in 2019 (see Figure 2 below).³ Not shown in the figure from the 2019 publication (national data are published only with a 2-3 year delay). The decline between 2017 and 2022 (the last year of currently available data) has been practically linear.

This presented figure appeared in 2019 in an article in Human Reproduction Open by Gleicher et al.,³ for the first time attributing declines in birth rate to the increasing number of so-called “add-ons” to IVF, which since 2010 have become parts of routine IVF without appropriate prior validation studies.

And as, of course, noted above, the year 2010 was also the year when opinions about science started to so obviously separate between Liberals and Conservatives. One, therefore, can now in retrospect also conclude that acknowledged damages to IVF outcomes from the premature inclusion of so many unvalidated “add-ons” into routine IVF practice may also have been a consequence of how society, as of that point in time, had changed how it looked at the generation of evidence in science.⁴,⁵ As ChatGPT educated us, in the years 2007 to 2012, smartphones became ubiquitous, with all of the societal consequences we are increasingly recognizing and—at least in their negative connotations—have started to address (note the recent smartphone ban for children under age 16 in Australia).⁶

Unquestionably, more than many other specialty areas in medicine, the fertility field, especially since 2010, has in many ways lost its scientific direction, and not only as demonstrated by declining IVF pregnancy and live birth rates since 2010. Even more importantly, despite rapidly increasing numbers of publications in the field that may suggest a different interpretation, the field, on a scientific level, has, for all practical purposes, really stagnated, as there really has been no substantial change in clinical practice in decades. Now we just have to decide whether it was the Liberals’ or the Conservatives’ doing. The only ones who, definitely, are not guilty are, of course, the moderates (like us)!

References

1. Cohen PN. Unreviewed preprint; December 6, 2025; https://osf.io/preprints/socarxiv/u95aw_v2?utm_ source=substack &utm_medium=email andhttps://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/u95aw_v2

2. Bowles N. The Free Press. TGIF. December 12, 2025.

3. Gleicher et al., Hum Reprod Open 2019(3):hoz017

4. Mundasad S. BBC. September 10, 2025. https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cyv64377z91o

5. Lensen S, Attinger S. Pursuit. The University of Melbourne, Australia, April 9, 2025. https://pursuit.unimelb.edu.au/articles/taking-a-close-look-at-the-evidence-behind-ivf-add-ons

6. Livingston H. BBC. December 10, 2025. https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cwyp9d3ddqyo

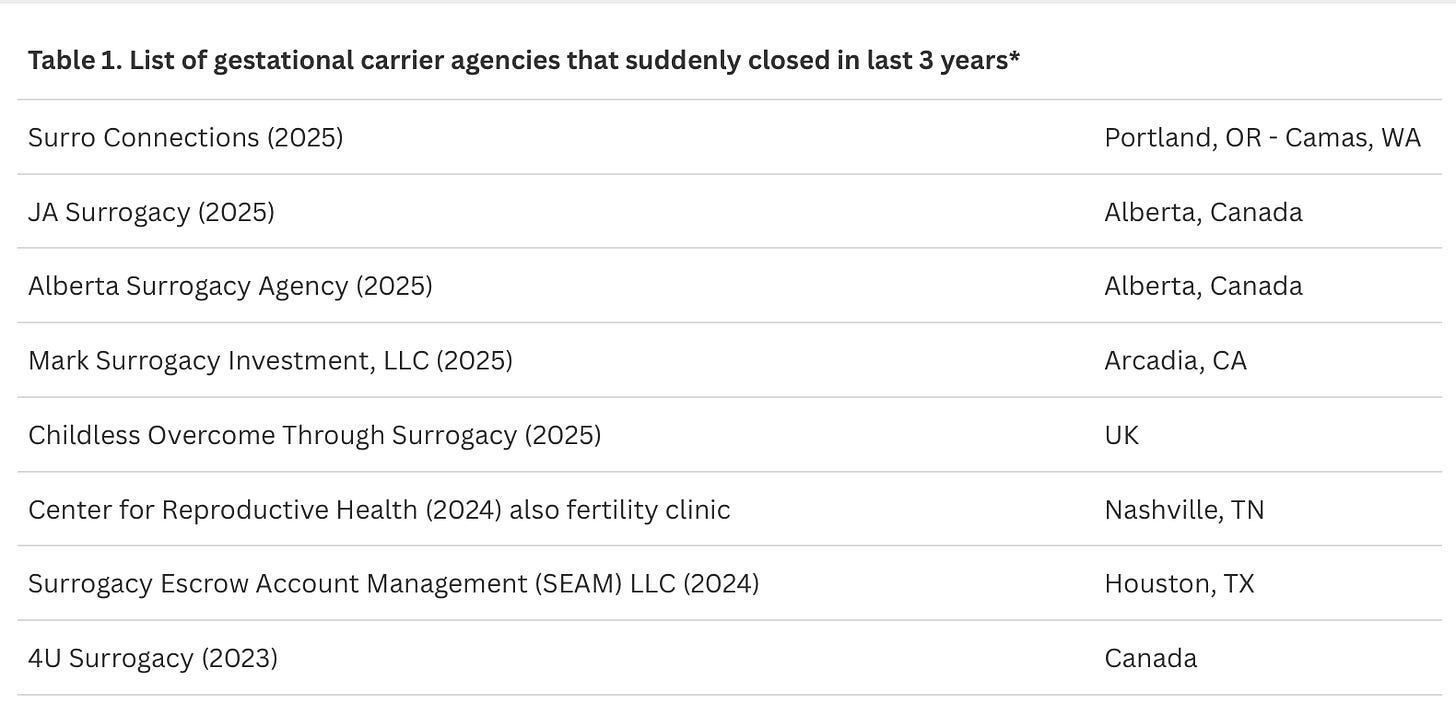

SURROGACY – Is it the dirtiest underbelly of infertility care?

The utilization of gestational carrier (GC) pregnancies, also called surrogacy pregnancies, has in recent years exploded, with increasing numbers involving patients who still could deliver themselves, but choose to use a GC more out of convenience than medical necessity, as was universally used to be practice when the concept of GCs started. With increasing utilization, the expected happened: costs went up and the quality of surrogacy agencies, as well as the through available GCs, declined. Also unsurprisingly considering the “big money” now flowing through surrogacy agencies, the field, indeed, therefore started to demonstrate a “dirty” underbelly, ultimately offering an impetus for this article on surrogacy practice when The New York Times (and other news outfits) recently reported the surprising closing of yet another surrogacy agency suddenly, leaving allegedly almost 150 pregnant GCs and their tentative recipients in limbo and millions of dollars missing. The Times recently also published a very relevant article regarding abuses of young Thai women as GCs by a rapidly expanding global fertility industry.

As a note of introduction, here is the definition of surrogacy (BOX 1):

BOX 1: Surrogacy is a legal arrangement in which a woman, known as a surrogate, agrees to carry and give birth to a child for another individual or couple, referred to as the intended parents. This process can be categorized into two main types: (i) Traditional surrogacy: In this arrangement, the surrogate is artificially inseminated with the sperm of the intended father or a sperm donor. The surrogate is, therefore, genetically related to the child born from the arrangement. (ii) Gestational surrogacy, where the intended mother’s egg is fertilized with the intended father’s sperm through in vitro fertilization (IVF). The resulting embryo is then implanted into the surrogate’s uterus, making her not genetically related to the child. To call the provider of the egg in a gestational surrogacy, a “surrogate” is, therefore, biologically and linguistically incorrect, and she, therefore, should be called a gestational carrier (GC), the terminology we will apply in this article.

We ask this provocative question because the current surrogacy landscape raises serious concerns about ethics, transparency, and patient safety. The growing number of commercial surrogacy arrangements, declining oversight, and recent scandals have prompted us to scrutinize whether surrogacy, once a compassionate medical solution, now exposes patients and GCs to significant risks and exploitation.

The impetus for this article was a recent article by Sarah Kliff in The New York Times on December 13, 2025, under the headline, “Parents-to Be Put Faith And Money in Surrogacy. Then the Agency Closed.”¹ The proprietor, Hall Greenberg, vanished, and with her, an estimated $5 million, leaving allegedly up to 150 pregnant GCs (quite a successful agency!) and their recipient couples in limbo.

For the CHR, the article did not come as a surprise because we heard this story before, and more than once. Unfortunately, surrogacy agencies have a very checkered history, and this description may even be a too benign interpretation of history. Stories like the most recent one involving an agency by the name Surro Connections in Portland, Oregon, and Camas, Washington, have been in the news every few years over and over again (Table 1).²

Because of these experiences, CHR has been advising its patients for many years to be careful in choosing a surrogacy agency. We also have established a very short list of recommended surrogacy agencies, which have to fulfill several preconditions: (i) We need to know the owners; (ii) We or colleagues we trust must have worked with the agency on at least three occasions; (iii) The agency had to be in business for at least five years; (iv) The agency must be licensed by New York State (even if located outside of the state).

And even if we recommend an agency, we recommend that our patients hire their own lawyers to review all the documents they are asked to sign, which are usually prepared by the agency. Moreover, before putting any money down, the CHR always strongly recommends that its patients let a CHR physician interview the prospective GC before our patients put down any money at the agency for the surrogacy cycle. Finally, we always recommend to our patients to make certain that at least a major part of the overall payment to the agency is in escrow and that this escrow is outside of the agency and independent of the agency.

AND THINGS HAVE GOTTEN WORSE – MUCH WORSE

And not only because of “dirty” agencies. Since the COVID pandemic ended—and it is not very clear why—the demand for GCs has dramatically increased. The CHR currently does likely more than five times the number of GC cycles than before COVID started, and we hear that these increases are observed in almost all IVF clinics that offer GC cycles, as well as, of course, in surrogacy agencies. That all the time new agencies are popping up is, therefore, not surprising.

With so rapidly increasing demand, it is also unsurprising that costs have significantly increased, While before COVID we used to advise the CHR’s patients that they could expect costs in the range of approximately $60,000-100,000 for GC and agency fees (including legal fees), we these days have to quote a range of at least $100,000 to $150,000, and these fees, of course, do not yet include IVF cycle costs for patient and her GC. Moreover, just in the week before this article was written, we learned from two distinct CHR patients that their total GC and agency costs exceeded $300,000 (both paid extra fees to their respective agencies to be advanced in their agencies’ waiting lists for GCs, in itself not a very ethical offer, though now almost routine at surrogacy agencies).

And then there is, of course, also the quality of available GCs. Here, too, it is not surprising that the greatly increased demand has produced negative effects on the clinical selection process for GC candidates, a process, of course, in principle conducted by surrogacy agencies. The CHR has seen a highly significant drop in the quality of GCs since COVID. As already noted before, we have recommended to CHR’s patients to let a CHR physician screen their potential GC before they make any payments to the agency. This usually involves a tele-consultation and laboratory test review (i.e., a review of the agency’s selection process). Before COVID, there was only rarely a need to recommend against a GC. Nowadays, it—unfortunately—has become quite common that we have to warn patients about facts they did not know about their GC based on the information they received from their agency.

THE CHINESE SURROGACY INVASION

was recently—under the heading, “The Chinese Billionaires Having Dozens of U.S.—Born Babies Via Surrogate”—subject of a lengthy article in The Wall Street Journal,³ led by the image below of Chinese video game executive Xu Bo, alleged—overall—to have more than 100 children, produced through pregnancies, utilizing “surrogacy” (which form is unclear). And he by no means is the only one.

When—as The Wall Street Journal article noted—a judge called Bo in 2023 into court for a hearing about multiple cases in which he was seeking parental rights for children born after surrogacy pregnancies, he appeared in court directly from China only electronically, expressing his hope of producing at least 20 U.S.-born GC children, all boys (who he considered “superior” to girls) who he, one day, wanted to take over his business.

As the article further reported, the judge was alarmed since surrogacy pregnancies were supposed to help people build families and what Xu described to the court his purpose to be did not even appear to represent parenting. Though courts usually quickly approve intended parents of a GC baby, the judge in this case denied the request for parentage, leaving the children of Bo in legal limbo.

China does not allow any form of surrogacy. Wealthy Chinese elites, therefore, are quietly having large numbers of U.S.-born babies, which, under currently applied U.S. law at the time of this writing (currently under review by the U.S. Supreme Court), also usually awards those children U.S. citizenship (and, therefore, also gives their parents a way toward citizenship).

According to The Wall Street Journal article, Bo’s company on social media claimed that Bo—in the U.S. alone—produced over 100 GC offspring (most likely a significant exaggeration, but who can know for sure?). Another wealthy Chinese, Wang Hui, is more modest and claims to have only 10 girls—according to The Wall Street Journal—conceived with the intent of marrying them off later to “powerful men.” A Los Angeles-based surrogacy attorney claimed to The Wall Street Journal to—recently—have helped a Chinese billionaire to have 20 children through surrogacy.

Most Chinese use of U.S. surrogates and GCs, however, involves more “standard” numbers of children and is often more motivated by social rather than medical reasons for using a surrogate or GC. Considering how sophisticated the “industry” surrounding the process has become, pregnancy with a surrogate or GC is often arranged without the Chinese genetic parent ever entering the U.S: His and/or her gametes are shipped to the U.S., and a baby is shipped back!

As The Wall Street Journal article also noted, even prominent Chinese government officials have used U.S surrogacy. Indeed, one such surrogacy led to the sudden 2023 “disappearance” of the Chinese Foreign Minister, Qin Gang, who fell from political grace after he was discovered to have an affair with a prominent female Chinese newscaster, which included the newscaster having a child in the U.S. through a GC (apparently with the Foreign Minister’s being the father), a fact Chinese supreme leader, Xi Jinping, apparently did not appreciate.

AND NOW PROBABLY THE WORST NEWS ABOUT SURROGACY: INTERNATIONAL SLAVE TRADE

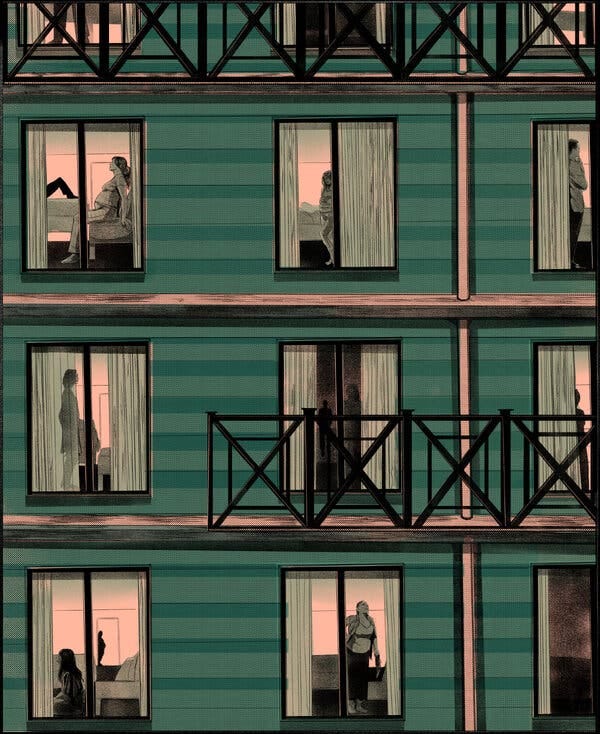

This is really the only way how what was recently (December 21, 2025) reported in The New York Times Magazine can be described (see image from this article below).⁴

By way of background, the article is also featured on the cover of The New York Times Magazine of December 21, 2025, under the heading, “They Don’t See Us As Human: Inside the Dark Corners of the Global Fertility Industry,” and was written by Sarah A. Topol, a New York Times contributor. In many ways, the article indeed describes the darkest corners of an increasingly global infertility industry, in this case mostly concentrating on the abuse of economically disadvantaged women in Thailand who—mostly through Chinese intermediaries—are flown over 4,000 miles to Tbilisi, the capital of Georgia, which, since the fall of the Soviet Union, has again been an independent country in the Caucasus Mountains. There, all kinds of things can—and usually will—happen to them: they may be inseminated as surrogates or have embryos transferred into their uteri as GCs, but they may also be used as egg donors, at times not even being informed that this was what was happening.

As the article described, they usually live in often abhorrent conditions in small, run-down apartments or even special buildings. The title of the article was “The Women of House 3,” which apparently offered better conditions than House 5 (allegedly housing hundreds of women) and to which women were moved from House 3 if they misbehaved.

That Armenia had also become the new “cheap” headquarters for medical tourism from the U.S. had not been a secret. Here at the CHR, we have observed this trend for several years, as we have noticed a small but steady increase in the number of patients who had traveled to Armenia before consulting with the CHR. That conditions in Armenia might be as described in this article for these poor women from Thailand was, however, unexpected. The article also claimed that many of these surrogates and GCs struggled with adequate nutrition, in both quality and quantity, which, of course, especially for women carrying a pregnancy, is anything but ideal. What, however, was most disturbing in this article were the very obvious analogies to sex trafficking rings in the ways in which these women were recruited, then shipped across borders into a new country, where they basically became unprotected slaves once their traffickers confiscated their passports.

Armenia is, of course, not the first country where these and similar abuses of women have occurred. Over a decade ago, it was India that offered a comprehensive and relatively inexpensive repertoire of fertility services, including gestational surrogacy in all of its forms. Once the Indian government shut that down, U.S. patients who needed these services at significantly lower costs than those offered in the U.S. moved to Ukraine. But then Russia invaded, and who can forget the large number of patients and newborn babies initially caught in Ukraine because of the war? Practically overnight, Armenia offered itself as an alternative.

Gestational surrogacy in all of its forms is, of course, not the only fertility treatment frequently involving medical tourism by U.S. patients, because many costs in the U.S. have become so prohibitive. Medical tourism for egg donation, likely even more popular, though—based on the CHR’s impression—appears to have peaked and now seems on the decline. The New York Times Magazine is, however, to be congratulated for having, in a relatively short time, published two important articles describing excesses associated with gestational surrogacy.

NEWS THAT REALLY SURPRISED US — for a change — has nothing directly to do with surrogacy agencies but, indirectly, may at least in some ways relate to the declining quality of GCs noted in the preceding paragraph. What came as a total surprise to us at the CHR—and, we believe, to most colleagues as well—was that our understanding of the clinical risks of GC pregnancies had to be completely revised. The assumption was that, because GCs usually are relatively young and carefully prescreened, GC pregnancies should be very low risk. But as recent studies have demonstrated, that is absolutely not the case. They are not even average-risk, but surprisingly frequently high-risk pregnancies.

Canadian investigators in 2024 compared pregnancy outcomes in Ontario between April 2012 and March 2021 in three distinct patient groupings: (i) 846,124 (97.6%) spontaneous and unassisted conceptions; (ii) 16,087 (1.8%) IVF pregnancies; and (iii) 806 (0.1%) GC pregnancies through IVF.⁵

Respective risks for severe maternal morbidity (SMM) were 2.3%, 4.3%, and 7.8%. Respective risks for severe neonatal morbidity were 5.9%, 8.9%, and 6.6%. Hypertensive disorders, postpartum hemorrhage, and preterm birth at less than 37 weeks were also significantly higher when contrasting gestational carriers with either comparison group. Among singleton births of more than 20 weeks’ gestation, a higher risk for SMM and adverse pregnancy outcomes was therefore seen among gestational carriers compared with women who conceived with and without assistance. Although gestational carriage was associated with preterm birth, there was less clear evidence of severe neonatal morbidity. The authors correctly concluded that potential mechanisms for higher maternal morbidity among gestational carriers require elucidation, alongside the development of special care plans for gestational carriers.

Though this was, of course, a retrospective study, with all of the well-known limitations of such studies, the large number of study subjects and the real-life results have to be considered astonishing, given prior expectations about GC pregnancies. Also considering that this study started in 2012, it seems unlikely that recent declines in GC quality significantly contributed to these results. Because these outcomes are so counterintuitive, the authors’ conclusion that the causes for the unexpectedly high morbidity of GCs must be elucidated therefore appears logical.

Convinced that our specialty has for decades been underestimating the importance of the immune system for normal human reproduction, it may be worthwhile to consider the fact that, in contrast to routine pregnancies, which usually are genetically semi-allografts, GC pregnancies are full allografts and therefore represent a much greater burden for the maternal immune system. An increased prevalence of prematurity and preeclampsia should therefore not surprise.

CONCLUSIONS — These findings, however, only reemphasize the importance of careful GC selection. They also mandate appropriate informed consent for GCs and their adequate protection from medical risks. It is important to point out the differences between being a GC and being an egg donor. While egg donation, of course, also carries some risks, the risks of pregnancy for the GC are obviously much greater than was known until recently and must, going forward, be included in the risk–benefit evaluation of every GC cycle.

GC cycles initially used to be restricted to women who simply had absolutely no chance of pregnancy. In the CHR’s longstanding opinion, the option of a GC pregnancy therefore still greatly prevails over the, in our opinion, over-the-top option of uterine transplants propagated by some colleagues. But we here at the CHR, and—as we hear from colleagues—other fertility clinics as well, see an increasing percentage of women using GCs to build their families who do not present with a strong medical indication and instead often use a GC simply “out of convenience” (some public figures included).

They are, of course, entitled to make these choices, just as GCs are entitled to undergo GC pregnancies if they choose to do so, though nowadays with appropriate informed consent by agencies and physicians. Recent events, the CHR felt, offered enough new material for thought regarding GC cycles to warrant this article.

References

1. Kliff S. The New York Times. December 13, 2025, pA13. https://www.nytimes.com/2025/12/10/health/surro- connections- surrogacy-closure.html

2. Avalos G. NBC New York. Updated July 33, 2024, https://www.nbcnewyork.com/news/local/surrogacy-money-scandal-parents-in-limbo-nightmare/5565355/

3. Long et al., The Wall Street Journal, December 13, 2025.

4. Topol SA. The New York Times Magazine. December 21, 2025, p22

5. Velez et al., Ann Intern Med 2024;177(11):1482-1488

A Piece of My Mind: The Shame That Medical Gender Transitions In Children & Young Adults Have Brought Upon Medicine

BRIEFING: Even though gender transition—at least to a significant degree—must be viewed as an endocrine event, quite remarkably, the subject almost does not exist in the infertility literature. And, though a little more visible in the general medical endocrinology literature, the gender transition practice is there, also anything but popular. One, therefore, has to wonder why that is. Not only have gender transition treatments in the lay press been subject to several major articles, but they also, of course, have become a political football in the increasing hostility between the political left and right. And that became especially apparent when it comes to gender transition treatments of children and teenagers. Yet despite increasing controversy, often still under increased secrecy, gender transition is still practiced in the US. Who does it and where, and what exactly they do is not only mostly unknown, but, in the absence of clinical guidelines from a credible professional body, is also practically impossible to objectively judge. And then, who else but The Free Press, once again, explained it all in a very recent article, which became the main motivation (and an important source) for this article.

I WILL BE BLUNT—and have no hesitation to acknowledge that I am unqualified to make personal decisions for adult patients, and that includes medical treatment decisions. Like most physicians, I, however, of course, do have opinions, indeed, at times strong opinions, especially in areas of medicine where I perceive myself as having special expertise. I will also express those opinions to patients loud and clearly, will in detail explain the reasoning behind them, but I will never attempt to impose them. In other words, I am well qualified to make recommendations and explain alternative options, but I am not qualified to make to then the decision for the patients (even if I am asked what I would do if this were my daughter asking; she, indeed, would get the same answer!)

Nor does the CHR have mandated practice patterns as a precondition for treatments (many IVF clinics, unfortunately, do; several IVF clinics, for example, refuse IVF cycles if patients don’t consent to PGT-A). CHR’s policies, however, of course, do not allow treatments that threaten a patient’s personal physical health and wellbeing.

And we, here at the CHR, very clearly differentiate between children and minors, and adults. What age, however, makes a minor an adult has remained controversial. On the one hand, we recruit 18-year-olds into the military; yet we allow purchases of alcohol only after age 21. One, of course, must ask how we can let them be old enough to die for us, in the military, yet don’t consider them mature enough to purchase alcohol.

How does that make sense? It, of course, doesn’t—but nobody seems really to care!

WE DO CARE—Here at the CHR, we do, indeed, profoundly care when it comes to children and still relatively immature adults getting gender-bending health care in this country in some of the nation’s most prominent hospitals. And this has been reflected in a whole series of articles on the subject in the CHRVOICE and The Reproductive Times in recent years which—we hope—has left nobody in doubt that, except in extreme cases of duress (there, of course, must always be an exception in medicine, a way out of rigid conformity), lifelong—mostly irreversible—physical changes should not be imposed on minors by anybody and, certainly not, by cabals of school teachers, administrators, and physicians conspiring behind the back of often unsuspecting parents.

We repeatedly noted in these articles our lack of understanding of why often well-credentialled physicians at prominent academic institutions jumped into this ethically so incredibly controversial new medical practice area by establishing gender transition services in pediatric units, often causing irreversible lifelong changes for females and males, children and teenagers, with hormonal transition treatments and even surgical procedures like bilateral mastectomies in young females. By 2023, over 100 pediatric gender clinics existed in the US offering such transition services.

Only very selectively reported in the lay press (no media outlet ultimately contributed to the disclosure of these practices to the lay public as much as The Free Press), the medical literature practically ignored the subject almost completely. All of this changed on February 9, 2023, when Jamie Reed, as she described herself in the introduction to a by now truly historical article in The Free Press, “a 42-year-old St. Louis native, a queer woman, and politically to the left of Bernie Sanders,” blew the whistle.1 (see the headline below).

I Thought I Was Saving Trans Kids. Now I’m Blowing the Whistle.

What made Jamie Reed blow the whistle is important to understand. We, therefore, continue to quote from the introduction of her article:

“My worldview has deeply shaped my career. I have spent my professional life providing counseling to vulnerable populations: children in foster care, sexual minorities, the poor. For almost four years, I worked at The Washington University School of Medicine Division of Infectious Diseases with teens and young adults who were HIV positive. Many of them were trans or otherwise gender nonconforming, and I could relate: Through childhood and adolescence, I did a lot of gender questioning myself. I’m now married to a transman, and together we are raising my two biological children from a previous marriage and three foster children we hope to adopt. All that led me to a job in 2018 as a case manager at The Washington University Transgender Center at St. Louis Children’s Hospital, which had been established a year earlier.”

I left the clinic in November of last year because I could no longer participate in what was happening there. By the time I departed, I was certain that the way the American medical system is treating these patients is the opposite of the promise we make to “do no harm.” Instead, we are permanently harming the vulnerable patients in our care.

Today I am speaking out. I am doing so knowing how toxic the public conversation is around this highly contentious issue—and the ways that my testimony might be misused. I am doing so knowing that I am putting myself at serious personal and professional risk.

Almost everyone in my life advised me to keep my head down. But I cannot in good conscience do so. Because what is happening to scores of children is far more important than my comfort. And what is happening to them is morally and medically appalling.”

We here at the CHR know very well how the biological and psychological effects of excessive androgen supplementation can manifest themselves in hypo-androgenic, infertile adult women. We, therefore, can very realistically envision how much more significantly the much higher androgen hormone dosages used in gender transition will then affect a 14-year-old girl who believes she wants to transition to become a boy. We, indeed, do not only imagine these horror stories, but we have now been living them for several years, while surgeons and often very prominent hospitals, seemingly just interested in the profit the sudden demand for transgender services generated, continue to feed the frenzy.

Once again, the Reed family helped us to understand the long-term consequences of female gender transition. Once again, The Free Press contributed its pages, when Jamie Reed’s husband (Roxxane Reed, see picture below). As she disclosed in her above-cited article, a “transman” decided to detransition and explained his/her motivations in yet another must-read article in The Free Press.2 Here is what he/she had concluded: “When Jamie Reed revealed the dangers of gender-affirming care for minors, I felt threatened. That’s because she was right. The gender affirming care model rushes vulnerable people toward major medical changes without stopping to understand the roots of their suffering.”2

This insight, of course, not only sounds logical but is especially relevant coming from somebody who has undergone a transition as an adult. Imagine what it must be like for a child or a teenager as she/he grow older! While regret after gender transition appears to be relatively rare,3 several young adults have, indeed, gone public as they, all for their own reasons, decided to detransition, obviously strongly suggesting that their original transition as a minor was not the right decision for them.4 It is, therefore, difficult to understand how anybody can question the notion that juveniles should not be transitioned until they are old enough to make such a decision for themselves.

What that age should be is, of course, also controversial, when on the one hand, 18-year-olds can enlist in the army, alcohol purchases are in the US often restricted to those above age 21, and recent research suggests that brains don’t mature fully till age 25 (or even later).

Why has the subject then remained so controversial?

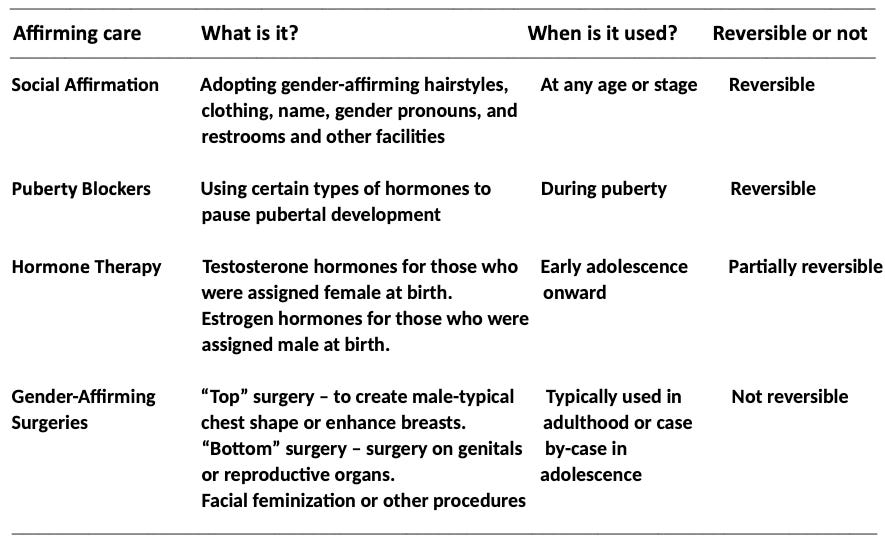

Because it has become political. One has only to take a look at the official website of the Office of Population Affairs of the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), which features a page on “Gender-Affirming Care and Young People,” which is preceded by the following announcement of the DHHS:

“Per a court order, HHS is required to restore this website to its version as of 12:00 AM on January 29, 2025. Information on this page may be modified and/or removed in the future subject to the terms of the court’s order and implemented consistent with applicable law. Any information on this page promoting gender ideology is extremely inaccurate and disconnected from truth. The Trump Administration rejects gender ideology due to the harms and divisiveness it causes. This page does not reflect reality and therefore theAdministration and the Department reject it.” 5

Obviously still a remnant of the prior Biden administration, the agency describes gender-affirming care as follows:

“Gender-affirming care is a supportive form of healthcare. It consists of an array of services that may include medical, surgical, mental health, and non-medical services for transgender and nonbinary people. For transgender and nonbinary children and adolescents, early gender-affirming care is crucial to overall health and well-being as it allows the child or adolescent to focus on social transitions and can increase their confidence while navigating the healthcare system.”

And the page then continues:

“Research demonstrates that gender-affirming care improves the mental health and overall well-being of gender diverse children and adolescents. Because gender-affirming care encompasses many facets of healthcare needs and support, it has been shown to increase positive outcomes for transgender and nonbinary children and adolescents. Gender-affirming care is patient-centered and treats individuals holistically, aligning their outward, physical traits with their gender identity. Gender diverse adolescents face significant health disparities compared to their cisgender peers. Transgender and gender nonbinary adolescents are at increased risk for mental health issues, substance use, and suicide. The Trevor Project’s 2021 National Survey on LGBTQ Youth Mental Health found that 52 percent of LGBTQ youth seriously considered attempting suicide in the past year. A safe and affirming healthcare environment is critical in fostering better outcomes for transgender, nonbinary, and other gender expansive children and adolescents. Medical and psychosocial gender affirming healthcare practices have been demonstrated to yield lower rates of adverse mental health outcomes, build self-esteem, and improve overall quality of life for transgender and gender diverse youth. Familial and peer support is also crucial in fostering similarly positive outcomes for these populations. The presence of affirming support networks is critical for facilitating and arranging gender affirming care for children and adolescents. Lack of such support can result in rejection, depression and suicide, homelessness, and other negative outcomes.”

Because of its many very obvious, outright false misrepresentations of important facts, this continuation of a formal government opinion (of the Biden administration) is, indeed, truly remarkable, though, to be fair, it also noted some correct observations. But that is not even the most offensive aspect of this document; the most remarkable aspect of this document published is the complete absence of any acknowledgment that some of the statements, even if one was willing to accept all of them as factually correct, by no means represent the scientific consensus and, at a minimum, therefore still must be considered to be controversial. The message the document conveys is, indeed, exactly the opposite.

This is confirmed by the Table below that completes the document and clearly supports all aspects of gender-affirming care—at least on a “case-by-case basis” in childhood and adolescence:

Who then can be surprised that the US medical establishment voiced no opposition to what was going on in so many hospitals and medical institutions, even though that stood—and to a degree still stands—in opposition to what happened in Europe. While especially in some Western European countries, similar practice trends started evolving as in the US, they reached an almost absolute halt after the so-called Cass Review was published in the UK in April of 2024, a three-year review conducted by a prominent British pediatrician, Dr. Hillary Cass, on behalf of the British National Health Service (NHS) in her role as Chair of the Independent Review of Gender Identity Services for Children and Young People.6

Key findings, and not only their content, but also their tone, reflective of obviously rather limited certainty, very clearly distinguished this report from the above-noted US DHHS document.

There is no simple explanation for the increase in the numbers of predominantly young people and young adults who have a trans or gender-diverse identity, but there is broad agreement that it is a result of a complex interplay between biological, psychological, and social factors. This balance of factors will be different in each individual.

There are conflicting views about the clinical approach, with expectations of care at times being far from usual clinical practice. This has made some clinicians fearful of working with gender-questioning young people, despite their presentation being similar to many children and young people presenting to other NHS services.

An appraisal of international guidelines for care and treatment of children and young people with gender incongruence found that that no single guideline could be applied in its entirety to the NHS in England.

While a considerable amount of research has been published in this field, systematic evidence reviews demonstrated the poor quality of the published studies, meaning there is not a reliable evidence base upon which to make clinical decisions, or for children and their families to make informed choices.

The strengths and weaknesses of the evidence base on the care of children and young people are often misrepresented and overstated, both in scientific publications and social debate.

The controversy surrounding the use of medical treatments has taken focus away from what the individualized care and treatment is intended to achieve for individuals seeking support from NHS gender services.

The rationale for early puberty suppression remains unclear, with weak evidence regarding the impact on gender dysphoria, mental or psychosocial health. The effect on cognitive and psychosexual development remains unknown.

The use of masculinizing/feminizing hormones in those under the age of 18 also presents many unknowns, despite their longstanding use in the adult transgender population. The lack of long-term follow-up data on those commencing treatment at an earlier age means we have inadequate information about the range of outcomes for this group.

Clinicians are unable to determine with any certainty which children and young people will go on to have an enduring trans identity.

For the majority of young people, a medical pathway may not be the best way to manage their gender-related distress. For those young people for whom a medical pathway is clinically indicated, it is not enough to provide this without also addressing wider mental health and/or psychosocially challenging problems.

Innovation is important if medicine is to move forward, but there must be a proportionate level of monitoring, oversight and regulation that does not stifle progress, while preventing creep of unproven approaches into clinical practice. Innovation must draw from and contribute to the evidence base.

CONSEQUENCES — that followed universally in almost all European countries following publication of the Kass Review were prohibitions of irreversible treatments—including puberty blockers—of children and young adults (age ranges differed between countries). But proponents of such treatments also in the UK were not willing to give up the fight and, as the BMJ recently reported, two studies—one at King’s College London and the other through the Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust in South London will now formally study the risks and benefits of giving puberty blockers to young people with gender incongruence. Despite opposition from some prominent scientists who, because of the young age of the study subjects, consider such studies “unethical” if there is “no likely clear benefit” for the children, both studies received ethical and regulatory approvals.7

THE MOST RECENT LITERATURE — Surprised by how little clinical experiences with transgender medicine had entered the literature in reproductive medicine, we recently were pleasantly surprised to find a narrative review in F&S Reviews, which appears to be evolving as the most interesting of the new F&S journals. The authors of this Review investigated the possibility of oocyte and sperm cryopreservation after medical transition. They concluded that there were differences in outcomes between transgender males and females: For transgender males, successful fertility preservation (of oocytes) turned out to be possible with relative ease even after transition, while for transgender females, the preservation of semen and estradiol supplementation reduced fertility potentials significantly.8

A RECENT BOMBSHELL ARTICLE — provided the incentive for this article, and where else is it from, but from a very recent posting of The Free Press.9 Under the heading, “We’re All Just Winging It”: What the Gender Doctors Say in Private.

The writer, Leor Sapir, in her article, fully reveals the ugly inhumanity behind gender medicine. In footage exclusively obtained by The Free Press, what the article calls “gender doctors” in the U.S. acknowledged that they perform life-altering procedures on vulnerable youth with no supportive evidence – and “are proud of it!”

All of those overheard conversations took place at a medical conference (closed to the press and “outsiders”) where “gender doctors”—as Sapir noted in her article—“allowed themselves to speak freely.” In a video from the 2021 conference of the US Professional Association for Transgender Health, a social worker from the Transgender Health Program at Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU) – of course a highly regarded academic institution especially in reproductive medicine—described an 18-year-old recent high school graduate who had expressed a desire to “look like Barbie down there,” as he was asexual and had no desire to ever have sex in the future.

Only relatively recently, as Sapir pointed out in her article, would such a young male patient have been given a psychological evaluation and mental health counseling. Now, “gender doctors” want to help young people (like this one) to achieve their gender goals.”

And the speaker, indeed, complained that—considering that the demand for such nonbinary gender modifications is rapidly growing—so-called surgical nullification procedures (individuals are left without any external genitalia) or penile preserving vaginoplasties (building a pseudo-vagina below the penis) “are not as accessible as they should be.” Another psychologist concurred and went even further by commenting that mental health professionals must “reframe” their role from being a gatekeeper to being a collaborator with the patient, meaning to “make sure that patients with serious mental health problems such as multiple personalities and psychosis are not excluded from gender surgery just because the team is uncomfortable operating on them.”

Much of what was revealed in Sapir’s article was based on court cases. Proponents of surgical transition procedures often relied on the “expertise” of the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) and its U.S. chapter (USPATH), claiming through its “Standard of Care Guidelines “unassailable guidance for how to treat young people with gender dysphoria or any other form of “distress” over one’s biological sex.

But, as it turned out, WPATH was anything but unassailable: In court proceedings, it was, indeed, alleged that WPATH had suppressed reviews of published evidence which had concluded that available evidence in support of hormonal and surgical treatments for minors was not at all credible. The society was also accused of financial conflicts of interest and eliminated age restrictions for such treatments for minors for “explicitly political reasons.” The Free Press article noted that the WPATH’s misconduct was documented by The New York Times, The Economist, The Washington Post, City Journal, and—as the only medical journal—the BMJ.

Hundreds of videos from medical conferences organized by WPATH and USPATH, which The Free Press was able to review, stemmed mostly from litigation in the state of Alabama. In her article, Sapir noted that these videos offered a window into how “gender physicians” speak differently to each other when they think outsiders aren’t listening, from what they tell the wider medical community and the public at large.”

She was especially incensed by those recordings about how clinicians openly acknowledged performing unproven (and, therefore, experimental) surgical treatments, without a protocol to be followed and/or ethical Review by an ethics board, as every human research requires. Moreover, she claimed to have heard from practitioners in those videos acknowledgments that their goal was “to fulfill the ‘embodiment-desires’ of their patients, whatever they may be, even if by doing so, this may require deviating from guidelines.”

To define the term “embodiment goals,” the article describes a case presented at the 2022 WPATH conference involving a 13-year-old boy who identified as nonbinary (“she/they”) whose stated goals were: “I want tits, and I want my parts to still work” (on a side note, his accompanying parent also identified as non-binary). Another case presented (OHSU physicians presented both of these cases) was a teen who “had realized that Frank-N-Furter from The Rocky Horror Show was his gender identity.”

At the 2022 WPATH conference in Montreal, a British endocrinologist (a consultant under UK titles) acknowledged that interventions are based on little or no evidence of efficacy. The article quoted him as—remarkably—acknowledging a disturbing truth:

“We are doing procedures here where we don’t have outcome data. So unless you want to go to individual ethics boards in each hospital to get ethics permission to do those surgeries because they’re on the edge of the field of medicine, you need to have a mechanism around you to support you. Otherwise, you could be vulnerable. That’s our feeling.”

The ignorance and narcissism of this physician are simply mind-blowing!

A, for-a-change female physician “had no problems with the novelty of nonbinary procedures” and even liked to offer her patients a “kind of Pinterest board” of gender-changing procedures. She was then also quoted as saying on a video that, “she (and other WPATH clinicians) were making it up as they went along.” More specifically, the article quotes her as saying: “I feel like we’re all just winging it, you know? And which is ok, you’re winging it too. But maybe we can just, like, wing together!”

The article then also addresses the resurgence of Eunuchism, which WPATH has reframed as the desire for castration as a gender identity issue. They may be aware of their identity already in childhood or adolescence and, of course, also represent a marginalized group, deserving of attention and understanding.

But the field is not standing still: A prominent Dutch practitioner in 2024 argued that the field of gender medicine was now ready to move beyond just a “logic of improvement” (i.e., achieving credible mental health benefits). It instead should be striving to achieve “gender euphoria” and “creative transfiguration,” with the latter meaning to view the body as a “gendered art piece” that can be made ours through transition-related interventions. Sapir appropriately pointed out the absurdity of these conclusions because what they would mean is that clinicians treating transgender patients no longer see themselves as treating a mental disorder but, for all practical purposes, as only plastic surgeons.

One, moreover, could also argue that they are pursuing insurance fraud by claiming mental health benefits on their insurance claims and are simply outright lying to patients and the public when claiming to be performing” lifesaving procedures.” How bizarre!

But the outrage goes even further: In internal discussions, many conference participants openly—and it appears even proudly—proclaimed that they routinely do not conduct mental health assessments of their patients or even assess their gender identity but, simply, execute the patients’ cosmetic “goals.” If this is a juvenile, such treatments may have irreversible consequences for that youth’s subsequent life. How shameful!

CONCLUDING — I am purposely leaving out politics from here discussion presented. This, of course, does not mean that I’m not worried about the potential circular impact political change can have on transgender medical care. President Biden considered the transgender movement “the civil rights issue of our times.” Suffice it to say, President Trump not only disagreed but issued an executive order that mandated federal agencies to end all medicalized transitions of minors. Who knows what New York’s mayor-elect Zohran Mamdani—a sworn advocate of youth transition—has in mind; he, during the election campaign, promised to spend $65 million for expanding and protecting gender-affirming care citywide for transgender youth as well as adults.

But within such a context, I am also pleased to quote Sapir’s article in regard to public opinion:

“More than seven in 10 Americans, including more than half of Democratic and Democratic-leaning voters, believe minors should not be offered puberty blockers or cross-sex hormones.”

Once more, the public appears to have more common sense than the so-called experts and, of course, politicians. If 70% of Democratic voters oppose puberty-suppressing and other hormonal treatments, even more Republican-leaning voters will have the same opinion. And if such large majorities even opposed gender-bending medical treatments, the opposition to irreversible surgical interventions must be even higher. A “hurrah” for common sense!

Common sense now also appears to have taken hold—at least in this regard—at HHS and, therefore, the Trump administration, which, through the Department of HHS, on December 18, 2025, with the story of Chloe Cole, a very obvious transgender childhood victim after detransitioning at the center, announced regulatory actions to end sex-rejecting procedures on minors.¹⁰

Now 21 years old, Cole went through a “medical transition” from female to male between the ages of 12-16. In a recent interview—and everybody should listen to it—she described how not only she was totally helpless at the time, not at all understanding what she was allowing to be done to her, but so were her parents who never thought she was really transgender but felt that “the odds were stacked against them” (by the health care system).

Standing at the podium alongside HHS Secretary Robert Kennedy, Jr. (“This is not medicine, this is malpractice”), Cole just wanted to be an advocate for children to protect them from all the suffering she had been exposed to as a child, from puberty blockers to testosterone injections, and a double mastectomy, adversely affecting her health irreversibly and permanently. To quote her one more time: “At the time when we started going through this as a family, there really were no resources that would speak to the reality of transgenderism, especially for children. Most people were not aware then that this was something that was even happening in our hospital systems.”

Cole also noted that—like many parents in these situations—her parents were told that, if they did not allow her to transition, she would likely commit suicide. Can anyone imagine the choices a medical professional in such a moment serves up to parents?! And we are quoting one more time: “My legal guardians were forced to make this decision under duress. But even if my parents had supported transitioning medically from the start, no parent or any adult, ultimately, has the right to determine whether a child gets to be chemically sterilized or mutilated.”

References

Reed J. The Free Press. February 9, 2025. https://www.thefp.com/p/i-thought-i-was-saving-trans-kids

Reed R. The Free Press. September 29, 2024. https://www.thefp.com/p/tiger-jamie-reed-detransition-wash-u-

transgender-affirming-care

Narayan et al., Ann Transl Med 2021;9(7):605

MacKinnon et al., JAMA Network Open 2022; 5(7):e2224717

Office of Population Affairs, DHHS, https://opa.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/2023-08/gender-affirming-care-young-

people.pdf. Accessed 12/9/2025.

Cass H. The Cass Review.

https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/ukgwa/20250310143933/https://cass.independent-review.uk/home/publications/final-report/

Waters A. BMJ 2025;391:r2478

Le et al., F&S Rev 2025;6(2):100093

Sapir L. The Free Press. December 3, 2025. https://www.thefp.com/p/were-all-just-winging-it-what- the utm_source=substack&publication_id=260347&post_id=180648411&utm_medium=email&utm_ content=share&utm_campaign=email-share&triggerShare=true&isFreemail=false&r=5dj1m5&triedRedirect=true

DiMella A. FOX News Digital. December 18, 2025. https://www.foxnews.com/health/detransitioner-chloe-cole-shares-complications-after-gender-procedures-i-am-grieving

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Press Release. December 19, 2025. https://www.hhs.gov/press-room/wtas-hhs-acts-bar-hospitals-performing-sex-rejecting-procedures-children.html

Goldman M. Axios. Updated December 18, 2025. https://www.axios.com/2025/12/18/trump-federal-payment-cuts-hospitals-gender-care