A Piece of My Mind: The Always Present Uncertainty in Medical and Scientific Certainty

By Norbert Gleicher, MD, Medical Director and Chief Scientist, at The Center for Human Reproduction in New York City. He can be contacted through the CHRVOICE or directly at ngleicher@thechr.com

Especially since the COVID pandemic, the credibility of medicine and science in general has, as repeatedly addressed in these pages, been under increasing scrutiny—and for good reasons, not only related to the pandemic. The basic question the public therefore rightly asks every time medical or scientific news comes up for debate is how much the presenting experts can be trusted—how certain can the public be that newly disseminated information is, indeed, correct and has been proven (i.e., in more scientific language, validated). This essay therefore addresses the issue of certainty in the science of medicine (including references to reproductive medicine) and concludes that uncertainty—at least for the foreseeable future (as nobody can yet fully foresee the future of A.I.)—will remain an integral part of all science since, otherwise, what would be the purpose of scientific investigations?

I ONCE AGAIN WILL BE BLUNT—every time I put my name on a publication, there is this nagging question in the back of my mind: Is what I am trying to communicate really true? And since I have published over 500 peer-reviewed papers (and many more book chapters), this concern has, of course, become a steady companion in my life as a physician-scientist.

Unsurprisingly, I am not alone. A recently published book by Prof. Adam Kucharski—a mathematician by training but in practice a Professor of Infectious Disease Epidemiology at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, where, according to his biography, he focuses on “making better use of data and analytics for epidemic preparedness and response”—addresses this issue. I indeed took the liberty of—at least to a degree—borrowing the idea for this essay, and segments of its title, from his most recent book, Proof: The Arts and Science of Certainty (Basic Books, 2025).

“Life is full of situations that can reveal remarkably large gaps in our understanding of what is true—and why it is true. This is a book about those gaps.”

—Adam Kucharski

The book received enormous exposure upon publication, with universally positive reviews in The Wall Street Journal,¹ The Lancet,² and Science magazine.³ It was also very favorably featured by Eric Topol, MD, on his Ground Truths podcast⁴ and noted positively by many other media outlets.

At least in part because of the trust medicine (and science in general) lost during the COVID pandemic, this subject has also recently received considerable attention in the medical literature,⁵ with one recent podcast noting that “the only certainty in medicine is uncertainty.”⁶

AMBIGUITY—of course—has an overwhelming presence in medicine and affects diagnoses, treatments, as well as treatment success versus failure. The two participants in the above-noted podcast indeed just published a paper in The New England Journal of Medicine in which, considering this fact, they described strategies to prepare trainees for the concept of clinical uncertainty.⁷

For a variety of reasons, complete knowledge in medicine is almost always unachievable, partially caused by limited scientific knowledge (i.e., epistemic limitations) and the effects of natural chance (so-called aleatoric causes). I personally have, over my career, become increasingly convinced that we have just started to peel the onion. Belonging to a generation that in medical school was still taught that every gene has only one function—and that we therefore would cure all medical problems in the world once we figured out what these functions were—the naïveté of those days now almost seems embarrassing.

Yet we are likely even today no less naïve than before, because under every new layer of the onion we remove, we find only more layers. I would indeed not be surprised if this is the mechanism by which evolution has secured the survival of species—by going from initially very simple redundancies (if A does not, as planned, go to B, there is a redundancy in the layer below that leads from A to B via C; and if A to B via C does not work, the next layer allows communication through D and/or E, etc.).

And we physicians do not help the process. Only a little more than a year ago, an article in Harvard Medicine attempted to address uncertainties in medicine. It identified misdiagnoses as perhaps the most important adverse consequence of our ignorance and noted the experience of an investigator trying to understand why, at that time, roughly 100,000 U.S. deaths per year were attributed to misdiagnoses.⁸ After reviewing several of these cases with a group of experts, the investigator was surprised that these experts—even when informed of the misdiagnoses beforehand—often still could not agree on a final diagnosis.

Which, of course, brings us to one of my favorite subjects: experts.

EXPERT OPINION—Medicine, and the world at large, relies on experts (how could I say otherwise, being myself considered an expert in at least some areas). But as the COVID pandemic so clearly demonstrated, experts can become a major problem, as expertise is usually restricted to relatively small areas. Problems experts are asked to address—including diseases—are, however, only rarely confined to such narrow domains.

Indeed, expertise suffers from the same error that once plagued our understanding of biology—namely, the belief that genes (or expertise) function in isolation. Just as we now know that genes interact in complex, polygenic ways and often have multiple functions, behavioral science has demonstrated that expertise almost never involves isolated knowledge. Even small medical subspecialties interact extensively with other, often conceptually distant, areas of medicine. This creates a major problem, aggravated by experts often not knowing what they do not know—and that, of course, does not apply only to medicine.⁹

Experts rarely possess special knowledge of seemingly unrelated areas of the body which, as we increasingly understand, often play major roles in their own domain. For this reason, they are frequently uninformed about these “other” areas of medicine and often resist their exploration to avoid exposing their ignorance. Our current separation of medical specialties is therefore badly outdated and—unless medical education is radically reformed—will continue to slow progress.

THE NEED TO REDEFINE MEDICAL SPECIALTIES—While traditional specialization has unquestionably advanced medical knowledge and improved treatments, it has also created a system in which patients are referred to too many specialists, leading to artificial and ever-smaller subspecialties. This system has become self-defeating and now requires fundamental change. Rising healthcare costs and lack of coordination between providers will otherwise increasingly impede progress.

Such change must be driven by advances in biological understanding—specifically a shift from organ- or symptom-based models to molecular, genetic, and multi-omic diagnoses—replacing traditional, reductionist, reactive medicine with proactive, tailored approaches that reflect the complexity of human biology and disease.

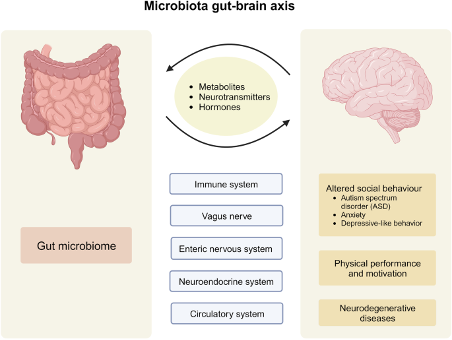

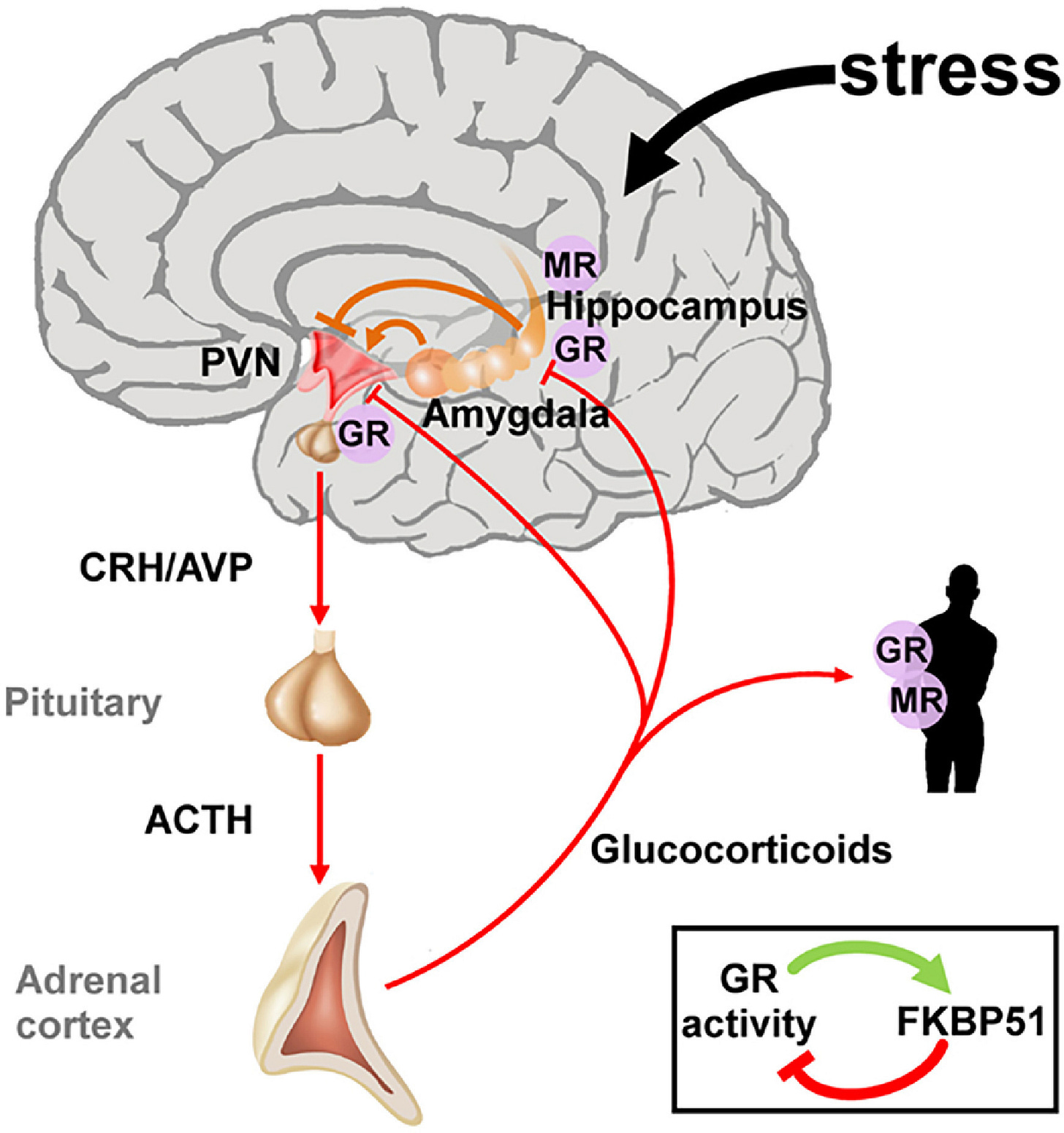

The human organism is deeply interconnected. Who, for example, would have guessed only 15–20 years ago that a brain–gut axis exists, allowing gut bacterial populations to affect the brain via bidirectional communication involving the vagus nerve,¹⁰ hormonal pathways such as the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis,¹¹ and immune signaling?

RELEVANCE TO THE INFERTILITY FIELD—We now know that the adrenal glands are closely linked to the ovaries—not only because they share an embryological primordium, but also because, as CHR investigators suggested several years ago, the HPA axis also extends to the ovaries.¹²

How did we reach this conclusion?

By demonstrating that many infertile women suffer from severe insufficiency of the adrenal zona reticularis, which under normal circumstances produces approximately 50% of a woman’s androgens. This insufficiency causes adrenal hypoandrogenism in virtually all cases of premature ovarian aging (POA)¹³ and phenotype-D polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS),¹⁴ rendering affected women infertile and often IVF-resistant unless androgen levels are normalized.

These observations alone suggest that it is only a matter of time before we discover how the gut microbiome affects these two female causes of infertility. This notion is further supported by the fact that the adrenal glands—after the ovaries—contain the highest density of anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) receptors, an observation that remains unexplained.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS—This brings us back to what Krammer titled his discussion of Kucharski’s book: “The Sisyphean quest for scientific certainty.”

Sisyphus, in Greek mythology, was condemned to an eternity of pointless labor—rolling a massive boulder uphill only to see it roll back down before reaching the summit. Krammer’s use of this analogy is apt: at least for the foreseeable future (we will see what A.I. can do for humanity), achieving “proof” in medicine resembles Sisyphus’s task.

Medicine can never reach the summit of absolute truth because we are perpetually peeling the onion—layer by layer—never knowing how many layers exist. The closer we believe ourselves to be to certainty, the more likely we are to discover additional layers still hidden beneath.

So where does this leave me and my persistent concern that some conclusions in my research or writing may be incorrect—or at least incomplete?

Paradoxically, I find this concern reassuring. Having such doubts appears not only appropriate but essential. I would argue that not having them is the real problem. We all know colleagues who are “never wrong” and harbor no doubts whatsoever (we call them at the CHR “believers”). For them, medicine is no longer science but religion. Their absence of doubt should itself be reason enough to view their pronouncements skeptically.

Ultimately, they are a primary reason why the credibility of medicine and science reached such a low point after COVID. Imagine if Fauci had answered even once during the pandemic with, “I don’t know,” or “I’m not sure.” But he didn’t.

References

Pools S. Proof: The Arts and Science of Certainty. Review. Wall Street Journal. June 6, 2025:A13.

Ball P. Proof: The arts and science of certainty. Lancet. 2025;405:1044-1045.

Krammer SMS. The Sisyphean quest for scientific certainty. Science. 2025. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/394926140_The_Sisyphean_quest_for_scientific_certainty

Topol E. Adam Kucharski: the uncertain science of certainty. Ground Truths (Substack). June 29, 2025.

Han PKJ. Uncertainty in medicine. Patient Educ Couns. 2021;104(11):2603-2606.

Ilgen JS, Dhaliwal G. Uncertainty in medicine. GeriPal Podcast. January 15, 2026. https://geripal.org/uncertainty-in-medicine-jonathan-ilgen-and-gurpreet-dhaliwal/

Ilgen JS, Dhaliwal G. Preparing trainees for clinical uncertainty. N Engl J Med. 2025;393:1624-1632.

Esty A. Navigating uncertainty in medicine. Harvard Medicine. July 2024. https://magazine.hms.harvard.edu/articles/navigating-uncertainties-medicine

Kowal Smith A. Why being an expert is dangerous—and how to fix it. Forbes. August 11, 2023. https://www.forbes.com/sites/annkowalsmith/2023/08/11/why-being-an-expert-is-dangerous-and-how-to-fix-it/

Loh K, et al. Microbiota–gut–brain axis and its therapeutic applications in neurodegenerative diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2024;9:37. doi:10.1038/s41392-024-01743-1

Ring M. An Integrative Approach to HPA Axis Dysfunction: From Recognition to Recovery. Am J Med. 2025;138(10):1451-1463.

Gleicher N, et al. Letter to the Editor: Including the Zona Reticularis in the Definition of Hypoadrenalism and Hyperadrenalism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102(9):3569-3570.

Gleicher N, et al. Hypoandrogenism in association with diminished functional ovarian reserve. Hum Reprod. 2013;28(4):1084-1091.

Gleicher N, et al. Reconsidering the Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS). Biomedicines. 2022;10(7):1505.