EDITORIAL: SURROGACY – The Dirtiest Underbelly of Infertility Care?

By The Editorial Team of The Center for Human Reproduction (CHR) in New York City. Editorial opinions, therefore, also represent the institutional opinions of The CHR.

The utilization of gestational carrier (GC) pregnancies, also called surrogacy pregnancies, has in recent years exploded, with increasing numbers involving patients who still could deliver themselves, but choose to use a GC more out of convenience than medical necessity, as was universally used to be practice when the concept of GCs started. With increasing utilization, the expected happened: costs went up and the quality of surrogacy agencies, as well as the through available GCs, declined. Also unsurprisingly considering the “big money” now flowing through surrogacy agencies, the field, indeed, therefore started to demonstrate a “dirty” underbelly, ultimately offering an impetus for this article on surrogacy practice when The New York Times (and other news outfits) recently reported the surprising closing of yet another surrogacy agency suddenly, leaving allegedly almost 150 pregnant GCs and their tentative recipients in limbo and millions of dollars missing.

As a note of introduction, here is the definition of surrogacy (BOX 1):

BOX 1: Surrogacy is a legal arrangement in which a woman, known as a surrogate, agrees to carry and give birth to a child for another individual or couple, referred to as the intended parents. This process can be categorized into two main types: (i) Traditional surrogacy: In this arrangement, the surrogate is artificially inseminated with the sperm of the intended father or a sperm donor. The surrogate is, therefore, genetically related to the child born from the arrangement. (ii) Gestational surrogacy, where the intended mother’s egg is fertilized with the intended father’s sperm through in vitro fertilization (IVF). The resulting embryo is then implanted into the surrogate’s uterus, making her not genetically related to the child. Surrogacy is a legal arrangement in which a woman, known as a surrogate, agrees to carry and give birth to a child for another individual or couple, referred to as the intended parents. This process can be categorized into two main types:

(i) Traditional surrogacy: In this arrangement, the surrogate is artificially inseminated with the sperm of the intended father or a sperm donor. The surrogate is, therefore, genetically related to the child born from the arrangement.

(ii) Gestational surrogacy: Where the intended mother’s egg is fertilized with the intended father’s sperm through in vitro fertilization (IVF). The resulting embryo is then implanted into the surrogate’s uterus, making her not genetically related to the child.

To call the provider of the egg in a gestational surrogacy, a “surrogate” is, therefore, biologically and linguistically incorrect, and she, therefore, should be called a gestational carrier (GC), the terminology we will apply in this article.

We ask this provocative question because the current surrogacy landscape raises serious concerns about ethics, transparency, and patient safety. The growing number of commercial surrogacy arrangements, declining oversight, and recent scandals have prompted us to scrutinize whether surrogacy, once a compassionate medical solution, now exposes patients and GCs to significant risks and exploitation.

The impetus for this article was a recent article by Sarah Kliff in The New York Times on December 13, 2025, under the headline, “Parents-to Be Put Faith And Money in Surrogacy. Then the Agency Closed.”¹ The proprietor, Hall Greenberg, vanished, and with her, an estimated $5 million, leaving allegedly up to 150 pregnant GCs (quite a successful agency!) and their recipient couples in limbo.

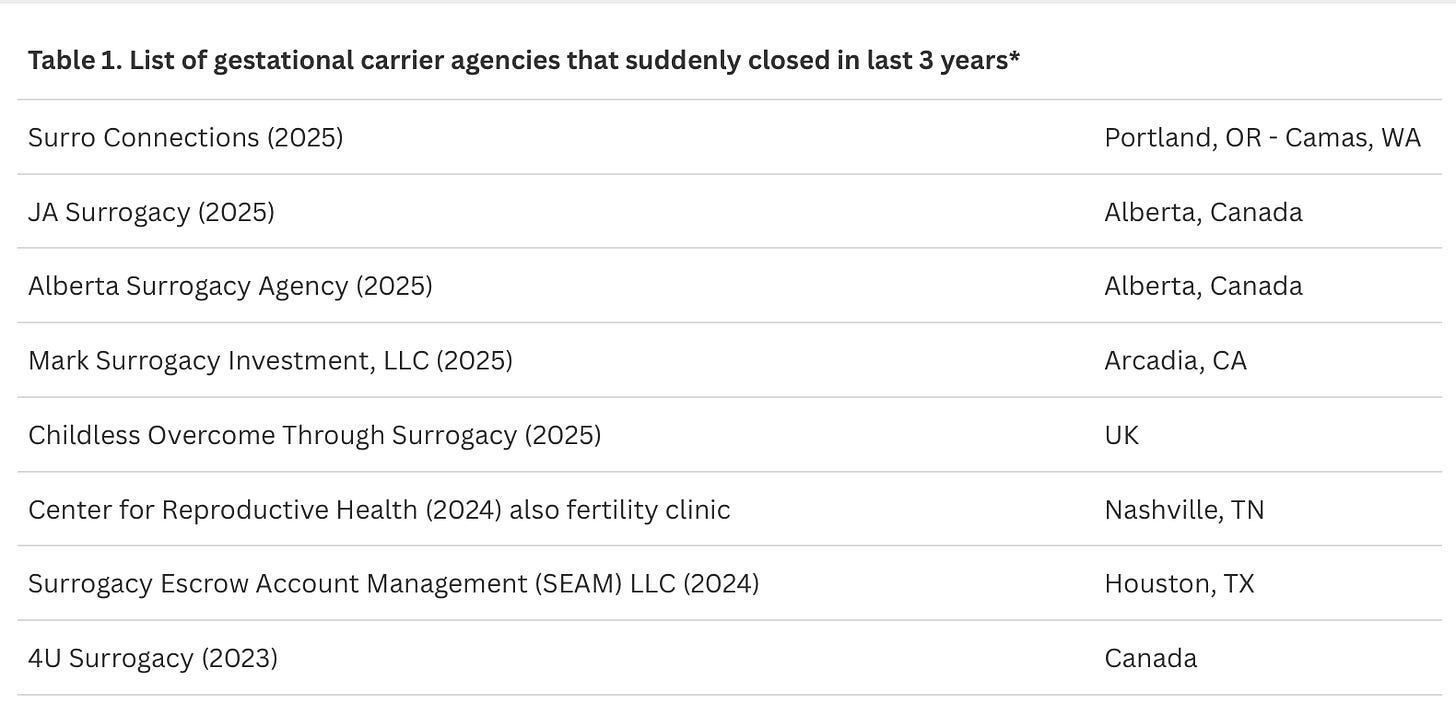

For the CHR, the article did not come as a surprise because we heard this story before, and more than once. Unfortunately, surrogacy agencies have a very checkered history, and this description may even be a too benign interpretation of history. Stories like the most recent one involving an agency by the name Surro Connections in Portland, Oregon, and Camas, Washington, have been in the news every few years over and over again (Table 1).²

Because of these experiences, CHR has been advising its patients for many years to be careful in choosing a surrogacy agency. We also have established a very short list of recommended surrogacy agencies, which have to fulfill several preconditions: (i) We need to know the owners; (ii) We or colleagues we trust must have worked with the agency on at least three occasions; (iii) The agency had to be in business for at least five years; (iv) The agency must be licensed by New York State (even if located outside of the state).

And even if we recommend an agency, we recommend that our patients hire their own lawyers to review all the documents they are asked to sign, which are usually prepared by the agency. Moreover, before putting any money down, the CHR always strongly recommends that its patients let a CHR physician interview the prospective GC before our patients put down any money at the agency for the surrogacy cycle. Finally, we always recommend to our patients to make certain that at least a major part of the overall payment to the agency is in escrow and that this escrow is outside of the agency and independent of the agency.

AND THINGS HAVE GOTTEN WORSE – MUCH WORSE

And not only because of “dirty” agencies. Since the COVID pandemic ended—and it is not very clear why—the demand for GCs has dramatically increased. The CHR currently does likely more than five times the number of GC cycles than before COVID started, and we hear that these increases are observed in almost all IVF clinics that offer GC cycles, as well as, of course, in surrogacy agencies. That all the time new agencies are popping up is, therefore, not surprising.

With so rapidly increasing demand, it is also unsurprising that costs have significantly increased, While before COVID we used to advise the CHR’s patients that they could expect costs in the range of approximately $60,000-100,000 for GC and agency fees (including legal fees), we these days have to quote a range of at least $100,000 to $150,000, and these fees, of course, do not yet include IVF cycle costs for patient and her GC. Moreover, just in the week before this article was written, we learned from two distinct CHR patients that their total GC and agency costs exceeded $300,000 (both paid extra fees to their respective agencies to be advanced in their agencies’ waiting lists for GCs, in itself not a very ethical offer, though now almost routine at surrogacy agencies).

And then there is, of course, also the quality of available GCs. Here, too, it is not surprising that the greatly increased demand has produced negative effects on the clinical selection process for GC candidates, a process, of course, in principle conducted by surrogacy agencies. The CHR has seen a highly significant drop in the quality of GCs since COVID. As already noted before, we have recommended to CHR’s patients to let a CHR physician screen their potential GC before they make any payments to the agency. This usually involves a tele-consultation and laboratory test review (i.e., a review of the agency’s selection process). Before COVID, there was only rarely a need to recommend against a GC. Nowadays, it—unfortunately—has become quite common that we have to warn patients about facts they did not know about their GC based on the information they received from their agency.

THE CHINESE SURROGACY INVASION

was recently—under the heading, “The Chinese Billionaires Having Dozens of U.S.—Born Babies Via Surrogate”—subject of a lengthy article in The Wall Street Journal,³ led by the image below of Chinese video game executive Xu Bo, alleged—overall—to have more than 100 children, produced through pregnancies, utilizing “surrogacy” (which form is unclear). And he by no means is the only one.

When—as The Wall Street Journal article noted—a judge called Bo in 2023 into court for a hearing about multiple cases in which he was seeking parental rights for children born after surrogacy pregnancies, he appeared in court directly from China only electronically, expressing his hope of producing at least 20 U.S.-born GC children, all boys (who he considered “superior” to girls) who he, one day, wanted to take over his business.

As the article further reported, the judge was alarmed since surrogacy pregnancies were supposed to help people build families and what Xu described to the court his purpose to be did not even appear to represent parenting. Though courts usually quickly approve intended parents of a GC baby, the judge in this case denied the request for parentage, leaving the children of Bo in legal limbo.

China does not allow any form of surrogacy. Wealthy Chinese elites, therefore, are quietly having large numbers of U.S.-born babies, which, under currently applied U.S. law at the time of this writing (currently under review by the U.S. Supreme Court), also usually awards those children U.S. citizenship (and, therefore, also gives their parents a way toward citizenship).

According to The Wall Street Journal article, Bo’s company on social media claimed that Bo—in the U.S. alone—produced over 100 GC offspring (most likely a significant exaggeration, but who can know for sure?). Another wealthy Chinese, Wang Hui, is more modest and claims to have only 10 girls—according to The Wall Street Journal—conceived with the intent of marrying them off later to “powerful men.” A Los Angeles-based surrogacy attorney claimed to The Wall Street Journal to—recently—have helped a Chinese billionaire to have 20 children through surrogacy.

Most Chinese use of U.S. surrogates and GCs, however, involves more “standard” numbers of children and is often more motivated by social rather than medical reasons for using a surrogate or GC. Considering how sophisticated the “industry” surrounding the process has become, pregnancy with a surrogate or GC is often arranged without the Chinese genetic parent ever entering the U.S: His and/or her gametes are shipped to the U.S., and a baby is shipped back!

As The Wall Street Journal article also noted, even prominent Chinese government officials have used U.S surrogacy. Indeed, one such surrogacy led to the sudden 2023 “disappearance” of the Chinese Foreign Minister, Qin Gang, who fell from political grace after he was discovered to have an affair with a prominent female Chinese newscaster, which included the newscaster having a child in the U.S. through a GC (apparently with the Foreign Minister’s being the father), a fact Chinese supreme leader, Xi Jinping, apparently did not appreciate.

NEWS THAT REALLY SURPRISED US

For a change, has nothing directly to do with surrogacy agencies but, indirectly, may at least in some ways relate to the declining quality of GCs, as we noted in the preceding paragraph. What came as a total surprise to us at the CHR, and we believe to most colleagues as well, was that our understanding about the clinical risks of GC pregnancies had to be completely revised: The assumption was that—because GCs usually are relatively young and carefully prescreened—GC pregnancies should be very low risk. But recent studies have demonstrated that this is absolutely not the case. They are not even average risk, but surprisingly, frequently high-risk pregnancies.

Canadian investigators in 2024 compared pregnancy outcomes in Ontario between April 2012 and March 2021 in three distinct patient groupings: (i) 846,124 (97.6%) spontaneous and unassisted conceptions; (ii) 16,087 (1.8%) were IVF pregnancies, (iii) 806 (0.1%) were GC pregnancies through IVF.3

Respective risks for severe maternal morbidity (SMM) were 2.3%, 4.3%, and 7.8%. Respective risks for severe neonatal morbidity were 5.9%, 8.9%, and 6.6%. Hypertensive disorders, postpartum hemorrhage, and preterm birth at less than 37 weeks were also significantly higher, contrasting gestational carriers with either comparison group. Among singleton births of more than 20 weeks of gestation, a higher risk for SMM and adverse pregnancy outcomes was, therefore, seen among gestational carriers compared with women who conceived with and without assistance. Although gestational carriage was associated with preterm birth, there was less clear evidence of severe neonatal morbidity. The authors correctly concluded that potential mechanisms for higher maternal morbidity among gestational carriers require elucidation, alongside developing special care plans for gestational carriers.

Though this was, of course, a retrospective study, with all of the well-known limitations of such studies, the large number of study subjects and the real-life results have to be considered astonishing, considering what expectations about GC pregnancies have been. Also, considering that this study started in 2012, it seems unlikely that recent declines in GC quality significantly contributed to these results. Because these outcomes are so counterintuitive, the authors’ conclusion that causes for the unexpectedly high morbidity of GCs must be elucidated, therefore, appears logical.

Convinced that our specialty has, for decades, been underestimating the importance of the immune system for normal human reproduction, it may be worthwhile to consider the fact that, in contrast to routine pregnancies, which usually are genetically semi-allografts, GC pregnancies are full allografts and, therefore, a much bigger burden for the maternal immune system. An increased prevalence of prematurity and preeclampsia, therefore, should not surprise.

CONCLUSIONS

These findings, however, only reemphasize the importance of careful GC selection. They, in addition, however, of course also mandate appropriate informed consent of GCs and their appropriate protection from medical risks. It is also important to point out the differences between being a GC and being an egg donor. While egg donation, of course, also carries some risks, the risks of pregnancy for the GC are obviously much greater than was known until recently and must, going forward, be included in the risk-benefit evaluation of every GC cycle.

GC cycles initially used to be restricted to women who simply had absolutely no chance of pregnancy. In the CHR’s longstanding opinion, the option of a GC pregnancy, therefore, still greatly prevails over the, in our opinion, over-the-top option of uterine transplants propagated by some colleagues. But we, here at the CHR, and, as we hear from colleagues, other fertility clinics as well, see an increasing percentage of women using GCs to build their families who really do not present with a strong medical indication and, indeed, often use GC simply “out of convenience” (some public figures included).

They, of course, are entitled to make these choices, just as GCs are entitled to go through GC pregnancies if they choose to do so, though nowadays, with appropriate informed consent by agencies and physicians. Recent events – the CHR felt - offered enough new material for thought regarding GC cycles to warrant this article.

References

Kliff S. The New York Times. December 13, 2025, pA13. https://www.nytimes.com/2025/12/10/health/surro-connections-surrogacy-closure.html

Avalos G. NBC New York. Updated July 33, 2024, https://www.nbcnewyork.com/news/local/surrogacy-money-scandal-parents-in-limbo-nightmare/5565355/

Long et al., The Wall Street Journal, December 13, 2025. https://x.com/Jon_Hartley_/status/2000029802343047635

Velez et al., Ann Intern Med 2024;177(11):1482-1488