How Confident Is Society Still in the Scientific Enterprise?

By Norbert Gleicher, MD, Medical Director and Chief Scientist, at The Center for Human Reproduction in New York City. He can be contacted through the editorial office of The Reproductive Times.

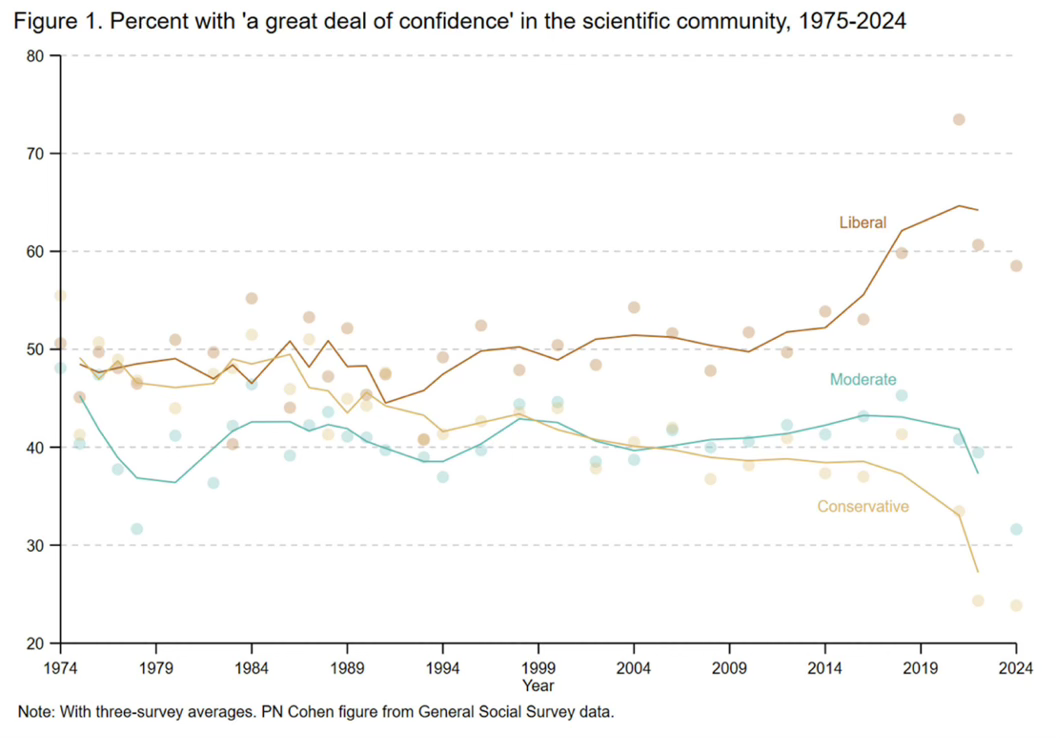

The business of medicine, of course, almost more than any other sector of the economy, is totally dependent on the confidence of society in science. For that reason, one of the weekly TGIF columns by Nelly Bowles in The Free Press, which the CHR’s Medical Director and Chief Scientist, Norbert Gleicher, MD, considers his favorite weekly media column, attracted his special attention. Bowles, in the column, reprinted a figure (Figure 1) from a recent (preprint) paper by a sociologist from the University of Maryland, demonstrating widely different perceptions of Liberals and Conservatives about their confidence in the scientific enterprise. Though she claimed “to need a microscope to spot the trends,” Gleicher found the trend curves fascinating and decided to go to the source paper, which disappointed him in the rather simplistic and obviously politically biased interpretation of observed trends by the author. He, therefore, decided to initiate an experiment on his own: Recognizing pretty obvious time points for changes in opinions among Liberals, Moderates, and Conservatives in Figure 1, he queried ChatGPT about societal developments that could have led to these changes. And ChatGPT’s responses were beyond interesting and informative.

How much confidence society still has these days in the scientific enterprise is—at least, in science circles and media—a not infrequently discussed question. It, of course, is also a crucially essential question for medicine, which, supposedly, is more and more built on science. The consensus in answering the questions has, however, increasingly been going in the wrong direction, with society seemingly progressively losing confidence, a widely attributed reason being the poor performance of government and its science advisors during the COVID pandemic.

But a recent preprint by Philip N. Cohen, PhD, a sociology professor at the University of Maryland,¹ and brought to our attention by Nellie Bowles in one of her brilliant weekly TGIF columns in The Free Press,² allows for somewhat different inferences.

They are best explained with a short introduction: Cohen updated data from two earlier studies to 2024, examining how U.S. societal confidence in science varies by citizens’ political identity. In other words, the study asked how Liberals, Moderates, and Conservatives from the mid-70s to now viewed science’s place in society. As this study mainly updated two former ones, existing differences between the three groups were already known. For this reason, we do not address the study design or its weaknesses and assume real-world experience from a large cohort.

Figure 1 below summarizes the data for the whole study period, including the materials for two earlier papers.

As this figure demonstrates, confidence in science was never really great; it, however, also was never, at least until roughly 2004-2009, as bad as it often was made out to be. But what really captured our attention and is fascinating is how political persuasion over time changed regarding how society has been feeling about science. And the most radical changes started already several years before COVID changed all of our lives. Society’s declining trust in science, therefore, has likely only very little to do with what happened during COVID.

Truly amazingly—if we are to believe this Figure—between the mid-1970s and the early 1990s, Conservatives and Liberals almost shared identical opinions about the credibility of science, with roughly half of both groups having a great deal of confidence in science. The outlier in those years was the Moderates who, with mild variability, have not much changed in their relative skepticism, and on average in only 40% have trusted science to these days.

But in the early 1990s, something interesting happened to Conservatives: Their trust in science started a steady decline, which has not stopped till today and, indeed, accelerated around 2015 and, ultimately, became a waterfall with the COVID pandemic, with trust in science expressed by just a smidgen above 25% of Conservatives after the pandemic ended.

In contrast, around 2010 (a very important date for reproductive medicine and especially IVF, to which we will return) Liberals, liberals suddenly started believing in science, increasing the percentage from approximately 50% to almost 65% of individuals who strongly trusted science, even though Nelli Bowles still felt “she needed a microscope to spot a trend.”

Cohen, the author, interpreted the results from a political perspective, as one might expect from a sociologist. He argued that the increasing divide between Liberals and Conservatives undermined the idea that modernity brings greater trust in science, which we agree with. However, he claimed this is not part of a general mistrust, since it does not show up among less conservative groups. He further argued that as the gap widens, right-wing leaders can more easily use distrust of science to rally conservative skeptics. This, he said, serves partisan goals. We disagree with Cohen here, as this ignores how Liberals also use their opinions for partisan purposes. Why must every sociologist always be on the political left?

So we decided to consult with ChatGPT as to what societal developments could have influenced these quite radical changes in the opinions of Liberals and Conservatives (without affecting Moderates), as Figure 1 very clearly demonstrates.

We first wanted to understand what, in the early 1990s, quite suddenly, might have adversely affected the credibility of science (at least among Conservatives). And here is what ChatGPT told us:

Several overlapping developments in the late 1980s to early 1990s weakened public confidence in science, not because science suddenly became worse, but because its authority, incentives, and visibility changed. Among those:

(i) The entanglement of science and industry became obvious, undermining the idea of science as a disinterested truth seeker.

(ii) The replication crisis began quietly with the “publish or perish” culture intensifying, journals favoring novel and positive results, and statistics being misused with so-called p-hacking and selective reporting.

(iii) With the end of the Cold War (1989-1991, the role of science in society changed. BEFORE, the importance of science in national defense and, space race offered unquestioned prestige. AFTER, science had to justify funding through policy relevance, and research became tied to political agendas, such as environment, health, and economics, looking like just another political weapon.

(iv) The spread of so-called postmodern skepticism in academia, based on claims, like science is a social construct; truth is contingent on power structures; objectivity is illusory, eroding trust in scientific authority.

(v) Media transformation and early internet effects, presenting conflicting expert opinions as equal, exaggerating uncertainty, reporting preliminary findings as facts, all making science appear inconsistent and unreliable.

(vi) Public scientific failures became visible, like the cold fusion claim collapsing in 1989, dietary advice reversals, medical treatment reversal, like for example postmenopausal hormone treatments (and here we go again right now), disease screening practices, etc.

(vii) Society shifted from “elite trust” to “institutional skepticism” and the early 1990s marked a transition with declines in trust of institutions (government, media, universities), rise in individual skepticism (do your own research, as we are doing here), and increasing questioning of authority. In other words, science lost its protected status as an unquestioned institution.

All of these explanations very well and credibly explained why society in the early 1990s would have undergone a quite dramatic change in its perception of science. These explanations, however, only further ask for answers for the increasingly contradictory behavior of Liberals who, in parallel to Moderates—at least until the end of the 1990s remained, more or less, unchanged in their attitude toward science, while conservatives, very clearly reflecting above noted societal effects pointed out by ChatGPT, as a logical consequence demonstrated clear declines in their appreciation of science.

In other words, it was the Conservative part of society (in contrast to Moderates and Liberals) who expressed progressive behavior changes in response to new societal realities, while Moderates and Liberals basically ignored all of these societal changes, i.e., “put their head into the sand.” Weren’t Conservatives, therefore—in contrast to how Cohen interpreted them in his paper—the real Progressives during this time period?

Now that ChatGPT gave us a very logical understanding of what the societal changes were in the late 1990s that separated Conservatives from Moderates and Liberals, let’s see what ChatGPT told us what happened, starting around roughly 2010 that led to a precipitous parting of ways between Liberals and Conservatives by ca. 2015, with Liberals, suddenly, becoming true believers in science and Conservatives basically losing almost all trust (see again Figure 1). We did this in two separate queries: In the first, we asked ChatGPT what societal developments around 2010 could have reduced trust in science, and in a second query, we asked what societal developments around 2010 could have enhanced trust in science, and ChatGPT, again, did not disappoint:

In response to the first query, ChatGPT offered the following answers: Around 2010, several overlapping societal and technological shifts in the U.S. converged in ways that (at least in Conservatives) eroded trust in science, even though scientific output was growing.

(i) The tipping point being 2008-2012, social media became a primary information source. Algorithms rewarded emotion, outrage, and novelty, not accuracy. Scientific uncertainty (normal in science) was reframed as weakness or dishonesty. Fringe and contrarian voices gained the same visibility as credentialed experts.

(ii) The politicization of scientific issues intensified, and several scientific topics became “identity-linked:” Climate change became a partisan marker rather than a technical question. Especially after the 2009 H1N1 flu season, vaccines became entangled with libertarian and parental-rights rhetoric. Evolution vs. creationism resurfaced in education debates, to later be followed by GMOs and fracking. As a consequence, trust in science increasingly depended on political affiliation rather than evidence.

(iii) A decline in gatekeeping by traditional media: BEFORE ~2010, science reporting passed through editors and specialist journalists; AFTER ~2010, newsrooms shrank dramatically, science desks were cut, and click-driven headlines oversimplified or sensationalized findings. Here are two examples: “One study says …” in place of reporting; treating preliminary or non-replicated findings as settled facts, with the effect being that the public saw science as inconsistent, flip-flopping, or hype-driven.

(iv) The replication crisis became public, with around 2010-2012, researchers openly (for the first time) acknowledging problems in psychology, biomedical sciences, nutrition research, and social sciences. Key issues that evolved were non-reproducible results, P-hacking, publication biases, and industry-funded studies, with the effect being that legitimate self-criticism inside science was interpreted by the public as proof that science was unreliable and corrupt.

(v) Growing distrust of institutions in general after the 2008 financial crisis must also be considered, as it had broad spillover effects after experts (economists and regulators) failed to predict or prevent the crisis. As a consequence credibility of the whole “expert class” suffered, and universities, government agencies, and corporations were seen as interconnected elites. The effect of all of this, in summary, was that scientists were increasingly viewed as part of a distrusted establishment.

(vi) The importance of personal experience rose over “expertise,” leading to a cultural shift toward “my truth,” anecdotal evidence, and influencers over institutions. Examples were: “vaccines harmed my child;” my diet cured me,” and “doctors ignored me,” and with such personal stories spreading faster and feeling more authentic than statistical data. Unsurprisingly, lived experiences, therefore, were often treated as superior to scientific consensus.

(vii) Education gaps in scientific literacy grew significantly, with many Americans lacking an understanding of probability and risk, lacking familiarity with how scientific consensus forms, and lacking awareness that uncertainty is not ignorance. And in addition, science communication often failed to explain uncertainty clearly and overpromised benefits and/or timelines. As a consequence, trust declined.

(viii) A cultural backlash against modernity and globalization, in addition, led to science becoming symbolically associated with global elites, secularism, technocracy, and loss of traditional identities, which fueled anti-intellectualism and suspicion of “experts telling us how to live.”

One cannot have lived through those years without having to conclude that ChatGPT, indeed, successfully summarized the evolving progressively defiant perception of science during those years, mostly expressed by Conservatives, but how would ChatGPT explain the evolving enthusiasm for science among Liberals? And here is the answer, and—once more—it was more than interesting:

It, first of all, correctly recognized the question as a “counter-question” to the prior question and, rather remarkably, addressed it by noting that, while trust in science fragmented after 2010, belief in its values (especially its usefulness) actually rose in many parts of U.S. society, thereby instantly offering explanations for what Figure 1 so obviously demonstrated. And here are nine of these explanations:

(i) Smartphones made science visibly useful in daily, personal, and immediate interaction because, around 2007-2012, smartphones became ubiquitous. Science, therefore, stopped being abstract and became understandable through GPS and satellite navigation, weather forecasting by the hour, medical apps, imaging, and diagnostics, through translation, speech recognition, AI assistants, fitness, sleep, and health tracking, with people suddenly experiencing science a “working” and not as “ideological.” Moreover, those skeptical of scientists now rely constantly on scientific outputs.

(ii) Rapid biomedical and health breakthroughs also contributed because post-2010 advances were highly visible, including CRISPR (2012), cancer immunotherapy, HIV treatments transforming life expectancy, mRNA platform development (pre-COVID), rapid genomic sequencing, prosthetics, bionics, and—yes—fertility technologies. As a consequence, medicine became a powerful demonstration of science’s tangible value.

(iii) After 2010, environmental events made science necessary and no longer optional because of more frequent extreme weather events, such as major droughts, hurricanes, and heat waves, all leading, even among climate skeptics, to rising insurance losses and infrastructure strain. Meteorology, engineering, and disaster science were suddenly seen as essential, and science gained value as a practical survival tool, even when conclusions were contested.

(iv) STEM economically became central. Cultural and economic shifts led to tech companies dominating the economy. STEM degrees were now linked to job security and upward mobility, coding and engineering were now promoted in schools, and “learn to code” became mainstream advice. As a consequence, science was valued as economic power, innovation, and national competitiveness.

(v) Especially after 2010, science was, in tech culture, reframed as “problem-solving,” and no longer as “authority”: less “as experts telling you what to think,” and more as experimentation, iteration, and hacking, which appealed to entrepreneur culture, DIY bio and maker movements, and science projects. In short, science is aligned with American values of pragmatism and innovation.

(vi) Data became a cultural language with explosions in data analytics, dashboards, evidence-based policy language, A/B testing, quantified self-movement, and people increasingly accepting “show me the data,” measurements as legitimacy, with the effect that even skeptics of institutions respected methods associated with science.

(vii) In some spaces (only) science communications improved, as new formats emerged, as Science YouTube (Kurzgesagt, Veritasium), podcasts (Radiolab, Science Vs), public intellectual scientists came on the scene, and better visualizations and storytelling took shape, and science became more accessible, human, and engaging.

(viii) A generational change also came into play as Millennials and Gen Z grew up with technology enabled by science, were more comfortable with complexity and uncertainty, and more likely to value evidence-based reasoning even if skeptical of institutions, so that aggregate belief in science‘s value increased through cohort replacement.

(ix) Even before COVID, smaller crises already showed a pattern of demonstrating science’s power (epidemics, like H1Ni1, Ebola, Zika), environmental disasters, and cybersecurity threats. COVID later dramatically reinforced this, with modeling, testing, and genomics becoming household concepts and science proving itself as indispensable even to critics.

ChatGPT thus correctly noted that after 2010, society in the U.S. increasingly held two ideas at once: “Science is extremely valuable” and “scientists and (their) institutions may not be trustworthy.” It appears that liberals, especially since 2015, have more subscribed to the former notion, conservatives to the latter, and Moderates, as always, continued to straddle the fence.

HOW ALL OF THIS RELATES TO REPRODUCTIVE MEDICINE

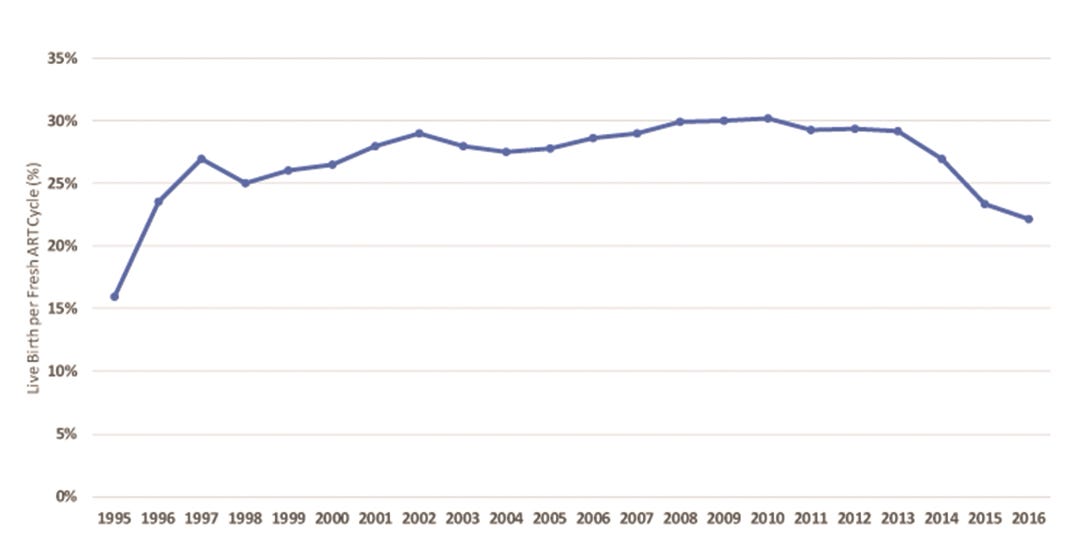

And now a final word about why all of this also has special relevance to reproductive medicine. The reason is that the year 2010 has also special meaning for in vitro fertilization (IVF). Until approximately the year 2010, clinical pregnancy and live birth rates in autologous IVF cycles had steadily improved since the inception of IVF. They plateaued around 2010 and, subsequently, uninterrupted, have been declining to this day, as we first reported in 2019 (see Figure 2 below).³ Not shown in the figure from the 2019 publication (national data are published only with a 2-3 year delay). The decline between 2017 and 2022 (the last year of currently available data) has been practically linear.

This presented figure appeared in 2019 in an article in Human Reproduction Open by Gleicher et al.,³ for the first time attributing declines in birth rate to the increasing number of so-called “add-ons” to IVF, which since 2010 have become parts of routine IVF without appropriate prior validation studies.

And as, of course, noted above, the year 2010 was also the year when opinions about science started to so obviously separate between Liberals and Conservatives. One, therefore, can now in retrospect also conclude that acknowledged damages to IVF outcomes from the premature inclusion of so many unvalidated “add-ons” into routine IVF practice may also have been a consequence of how society, as of that point in time, had changed how it looked at the generation of evidence in science.⁴,⁵ As ChatGPT educated us, in the years 2007 to 2012, smartphones became ubiquitous, with all of the societal consequences we are increasingly recognizing and—at least in their negative connotations—have started to address (note the recent smartphone ban for children under age 16 in Australia).⁶

Unquestionably, more than many other specialty areas in medicine, the fertility field, especially since 2010, has in many ways lost its scientific direction, and not only as demonstrated by declining IVF pregnancy and live birth rates since 2010. Even more importantly, despite rapidly increasing numbers of publications in the field that may suggest a different interpretation, the field, on a scientific level, has, for all practical purposes, really stagnated, as there really has been no substantial change in clinical practice in decades. Now we just have to decide whether it was the Liberals’ or the Conservatives’ doing. The only ones who, definitely, are not guilty are, of course, the moderates (like us)!

References

Cohen PN. Unreviewed preprint; December 6, 2025; https://osf.io/preprints/socarxiv/u95aw_v2?utm_

Bowles N. The Free Press. TGIF. December 12, 2025.

Gleicher et al., Hum Reprod Open 2019(3):hoz0174.

Mundasad S. BBC. September 10, 2025. https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cyv64377z91o5.

Lensen S, Attinger S. Pursuit. The University of Melbourne, Australia, April 9, 2025. https://pursuit.unimelb.edu.au/articles/taking-a-close-look-at-the-evidence-behind-ivf-add-ons6.

Livingston H. BBC. December 10, 2025. https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cwyp9d3ddqyo