Preimplantation Genetic Testing for Aneuploidy (PGT-A) Biology Behind the Labels and Hope After the Verdict: Perspectives on Transferring “Abnormal” Embryos From the Patients Who Said YES

Sonia Gayete-Lafuente, MD, PhD, is a Clinical Research Fellow at the FRM and the CHR and can be reached through the editorial office of The Reproductive Times.

*This publication is the edited version of an article that appeared in the September-October issue of the

CHR VOICE.*

Preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy (PGT-A) was introduced with the promise of improving in vitro fertilization (IVF) success by selecting chromosomally “normal” embryos for transfer and has become mostly unquestioned routine practice in many IVF clinics. Marketed worldwide as a tool to improve pregnancy rates, reduce miscarriage, and ensure the birth of healthy babies, it easily captured the hopes of patients already carrying the physical, emotional, and financial burdens of infertility. However, while the idea of chromosomal testing of embryos may on first impression sound reassuring, reality is more complicated and the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM, including SART) in September of 2024, finally, in public policy statement concluded that PGT-A, after over 20 years of utilization, still has not demonstrated any clinical outcome benefits for IVF and in some patient sub-groups even reduced pregnancy and live birth chances.

Though the CHR does offer PGT-A to its patients, we, since 2007, in a very large majority of cases have not recommended its use. Concluding that PGT-A in many patients actually reduces pregnancy and live birth chances, the CHR in 2014 started selective embryo transfers by PGT-A of as “aneuploid” reported embryos and in 2015 was the first IVF center in the world to report chromosomal-normal pregnancies following such transfers. Consequently, from all over the world, patients with only “abnormal” embryos after IVF + PGT-A have been moving their “abnormal” embryos to the CHR after their transfers are refused at their primary IVF clinics.

The CHR is maintaining a case registry for all of these “abnormal” transfers, which is periodically updated in publications.

As most IVF clinics in the U.S. and elsewhere in the world still refuse transfers of “abnormal” embryos, the CHR has been accumulating such “abnormal” embryo transfers from all over the world. This offered the opportunity for a long-term collaboration of the CHR in a study with bioethicist Shizuko Takahashi, MD, PhD, initially at Tokyo University and now at the University of Singapore, on patients who chose to transfer their “abnormal” embryos at our center. The purpose was to learn factors that shaped their decision-making process in having allegedly “abnormal” embryos transferred.

The study—currently submitted for publication—revealed a deep emotional toll of PGT-A when results are misunderstood, oversimplified, or used in a way that limits patient choice and pregnancy chances, with more details currently not disclosable until the paper has been published. The study’s results, however, are discussed in this article made comments regarding PGT-A.

The illusion of certainty

Despite fundamental technical flaws and growing evidence of its unreliability and its potentially harmful clinical effects on many women in IVF, among the various embryo selection methods promoted in IVF during recent years, preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy (PGT-A) has undoubtedly been most successfully marketed. While it is presented as a tool to identify embryos with the best chances of live birth, it also carries unacceptably high false positive rates that can create confusion and lead to several lost opportunities for infertile patients.

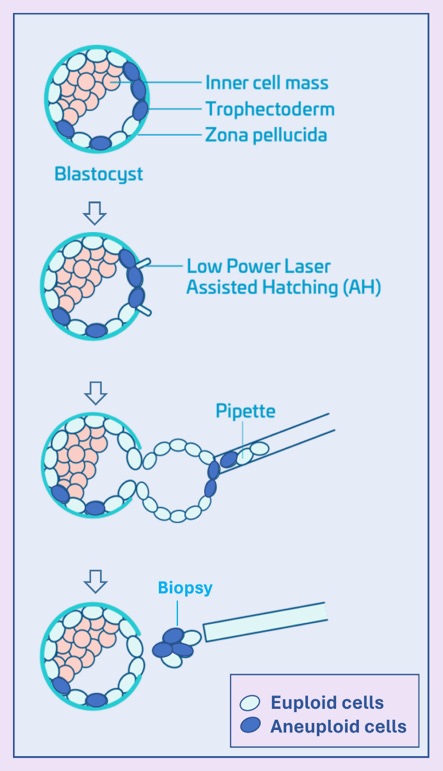

For some context, PGT-A involves a biopsy of the trophectoderm (See Figure below), removing on average 5–6 cells from a blastocyst that usually contains at least ca. 250 cells. The chromosomal makeup of this tiny DNA sample of 5-6 cells is then used to determine whether an embryo is labeled “euploid” (normal), “aneuploid” (abnormal), or “mosaic” (a mixture of normal and abnormal cells). The main technical problem is that the biopsy may not reflect the chromosomal status of the inner cell mass (the group of cells that develop into the fetus) or of the whole embryo. Moreover, biopsies are taken from the trophectoderm, which becomes the placenta, and not from the so-called inner cell mass that becomes the fetus. And the placenta is by now well known to, in most cases, continue to contain islands of aneuploid cells until birth.

Mosaicism is common at early stages of development. Growing evidence, moreover, has demonstrated that, especially within the inner cell mass, some embryos can, downstream from blastocyst-stage when embryos are biopsied in PGT-A, “self-correct.” This means a substantial proportion of embryos labeled “abnormal” by PGT-A may, in fact, be nevertheless capable of producing healthy pregnancies. Indeed, the CHR was the first IVF center to demonstrate that transfers of embryos by PGT-A, as “abnormal” reported embryos often will result in euploid pregnancies and delivery of euploid offspring. We, indeed, since also demonstrated that pregnancy and live birth rates from such transfers are unexpectedly high.

When results close doors

The path from biopsy to PGT-A result is rarely straightforward and represents an emotional rollercoaster: Hope rises during stimulation and retrieval, tension builds while awaiting results, and shock or despair can set in following “abnormal” PGT-A reports. Confusion often arises when personal hopes collide with science and statistical results. In most fertility clinics in the U.S, as well as internationally, all (or at least almost all) “abnormal” embryos will still not be transferred, not even selectively. In many centers, they, indeed, are still routinely discarded.

IVF cycle outcomes can lead to devastating and profound emotional crashes when all embryos are reported to be (allegedly) abnormal and, therefore, patients are usually informed that no embryo transfer is possible. Patients, indeed, often perceive such outcomes as a final verdict concerning their ability to conceive with the use of their own eggs.

The distress is not only about losing embryos, but about losing what those embryos represent, a unique and irreplaceable opportunity for parenthood. For couples with low functional ovarian reserve and/or advanced age, leading to only retrievals of a few or even no embryos, attempts at producing more embryos often become physically, emotionally, and financially unrealistic. When they then in addition are denied transfers of their own “abnormal” embryos, the patients’ only remaining chance of having a biological child may have been taken away not by biological realities but, simply, by the self-centered and grandstanding policy of IVF clinics, as published data are by now irrefutable that carefully selected “abnormal” embryos for transfer not only offer surprisingly good pregnancy and live birth rate (of course, age-specific), but are also very safe in their clinical outcomes (latest publications by our group in reading list at the end of this article: Patrizio P. et al., 2019; Barad D.H. et al., 2022; Gleicher N. et al., 2023).

Such denials, therefore, can be deeply triggering. Unsurprisingly, PGT-A, therefore, has attracted the attention of the plaintiff bar, with, for the first time, in 2024, several class action suits being filed around the country, accusing (at this point only) PGT-A laboratories of misrepresenting the PGT-A test to the public.

By having transferred “abnormal” embryos selectively for over a decade for patients from all over the world, the staff of the CHR has been witnessing expressions of these feelings on innumerable occasions and has been attempting to communicate their importance, to this point, unfortunately, only with limited success, through published papers and oral presentations at conferences to the whole infertility field. Still, unfortunately, only a relatively isolated voice among fertility clinics, those efforts, as of this point, have to be judged as only partially successful because, though in 2024 even ASRM/SART now formally acknowledged the lack of any significant clinical utility of PGT-A on IVF outcomes in general populations, PGT-A utilization in the U.S. and around the world is still increasing.

What patients are telling us

To better understand patients’ lived experiences with utilization of PGT-A in association with IVF for infertility, the CHR recently collaborated with Shizuko Takahashi, MD, PhD, a very prominent Japanese medical ethicist, currently on the faculty of Singapore University, on a qualitative study, soon to be published, exploring patients’ perspectives on transferring embryos by PGT-A labeled as “abnormal.”

Through in-depth interviews with many of the CHR’s patients who, at other IVF clinics around the world, went through multiple IVF cycles and then, usually because denied at the clinics where they had performed their IVF cycles, decided to transfer their “abnormal” embryos at the CHR, the study found that many described a process of having to unlearn the authority of genetic testing and reframing their own decisions as morally reasoned acts of reproductive agency.

Since our manuscript has not been published yet, we, as of this point, are not at liberty to go into further detail regarding the results of the study, but will, of course, do that in these pages after publication of the paper (with reference). What we can reveal is that decisions to transfer “abnormal” embryos are not reckless acts of desperation but deliberate and ethically framed choices.

Most importantly, the patients’ voices question widely held assumptions about PGT-A and very much challenge rigid embryo transfer policies.

Informed consent must be more than a signature

Given the above-discussed complexities and based on our study’s findings, informed consent for PGT-A must go far beyond just being a checklist. It should be evidence-based, dynamic, honest, and never paternalistic. Nor should it ever be imposed (some U.S. clinics refuse to perform IVF cycles if patients do not agree to PGT-A) or be offered by only assumed procreative beneficence.

Additionally, we must also consider that, even when transfer is permitted in a cycle, the following emotional burden is heavy: Patients must acknowledge the likely elevated risks of implantation failure and/or miscarriage, and, fortunately, only rarely, the possibility of an ongoing pregnancy with a chromosomal abnormality. They must also prepare for follow-up testing, including noninvasive prenatal testing (NIPT) at ca. 10 weeks of gestational age and amniocentesis between 15 and 20 weeks (as recommended by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, ACOG). Crucially, this conversation should happen before testing is ordered and, of course, especially continue if results are unexpected.

At the CHR, we strictly follow this very careful approach when counseling patients who are considering transfers of “abnormal” embryos. Of course, the conversation is individualized to the assessment of PGT-A results of their embryo cohort, as it is known by now that some chromosomal abnormalities are associated with higher risks of miscarriage than others, and that certain anomalie, such as trisomy 21 (Down syndrome), trisomy 18 (Edwards), trisomy 13 (Patau) and others, as well as sex chromosome abnormalities such as 45 XO (Turner) or 47 XXY (Klinefelter), are potentially viable (i.e., can give birth). In fact, we mostly only recommend against embryo transfer when such potentially viable chromosomal abnormalities are reported, though we still respect a patient’s decision if, after full disclosure, she nevertheless chooses to proceed with a transfer.

The possibility of a potentially surviving aneuploidy being a false-positive diagnosis is not different from other chromosomal abnormalities. It, therefore, is not surprising that we in such cases have seen chromosomal normal as well as abnormal pregnancies.

We, in other words, fully recognize that patients’ choices are made based on deeply personal reasoning, hopes, and beliefs which clinicians may not always fully grasp (we, of course, also do not have to agree with them); but we must always respect them and respect the fact that those embryos are not our, - but the patients’ legal property. We found that by proceeding in this way, regardless of the outcome, patients feel appreciated, are themselves appreciative, grateful, and to a significant degree at peace with their decisions.

Balancing perfection and possibility: A shared responsibility

Our research highlighted that patients understand biological complexities when appropriately explained, which allows them to make reasoned choices. As noted before, PGT-A, in over 20 years of clinical utilization under different names, has never been able to identify any outcome benefits for IVF cycles. It, however, very clearly adversely affects the cumulative pregnancy chance of every IVF cycle because every unnecessarily unused or discarded embryo has, of course, a negative effect on cumulative pregnancy chances. And that PGT-A either does not use or discards embryos with pregnancy potential can no longer be denied.

Especially for patients with small embryo numbers, PGT-A, therefore, may be the reason why they don’t even reach embryo transfer. Clinicians, therefore, must resist the temptations to pursue other IVF cycle goals than the one patients clearly favor above all other cycle outcomes, as several studies have clearly demonstrated, and that is the quick achievement of pregnancy!

This means that the pursuit of the “perfect” embryo, the “best clinic rates,” and, of course, financial incentives for IVF clinics, should not be decisive in choosing fertility treatments. Clinicians bring expertise to the table, but the patients bring values, goals, tolerance for risks, and fate, as well as emotional resilience, to get to a healthy baby whenever possible. When that is not possible any longer, then it is the physician’s responsibility to explain this fact and suggest a meaningful path forward.

References

Gleicher N, Gayete-Lafuente S, Barad DH, Patrizio P, Albertini DF. Why the hypothesis of embryo selection in IVF/ICSI must finally be reconsidered. Hum Reprod Open. 2025;2025(2):hoaf011

Gleicher N, Barad DH, Patrizio P, Gayete-Lafuente S, Weghofer A, Rafael ZB, Takahashi S, Glujovsky D, Mol BW, Orvieto R. An additive opinion to the committee opinion of ASRM and SART on the use of preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy (PGT-A). J Assist Reprod Genet. 2025;42(1):71-80.

Barad DH. PGT-A “perfect” is the enemy of good. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2023 Jan;40(1):151-152.

Gleicher N, Patrizio P, Mochizuki L, Barad DH. Previously reported and here added cases demonstrate euploid pregnancies followed by PGT-A as “mosaic” as well as “aneuploid” designated embryos. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2023;21(1):25.

Gleicher N, Barad DH, Patrizio P, Orvieto R. We have reached a dead end for preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy. Hum Reprod. 2022;37(12):2730-2734.

Barad DH, Albertini DF, Gleicher N. In science, truth ultimately wins, and PGT-A is no exception. Hum Reprod. 2022;37(9):2216-2218.

Barad DH, Albertini DF, Molinari E, Gleicher N. IVF outcomes of embryos with abnormal PGT-A biopsy previously refused transfer: a prospective cohort study. Hum Reprod. 2022;37(6):1194-1206.

Patrizio P, Shoham G, Shoham Z, Leong M, Barad DH, Gleicher N. Worldwide live births following the transfer of chromosomally “Abnormal” embryos after PGT/A: results of a worldwide web-based survey. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2019;36(8):1599-1607.