Reproductive and Some General Immunology

Learning something new – activation of the vagus controls inflammation

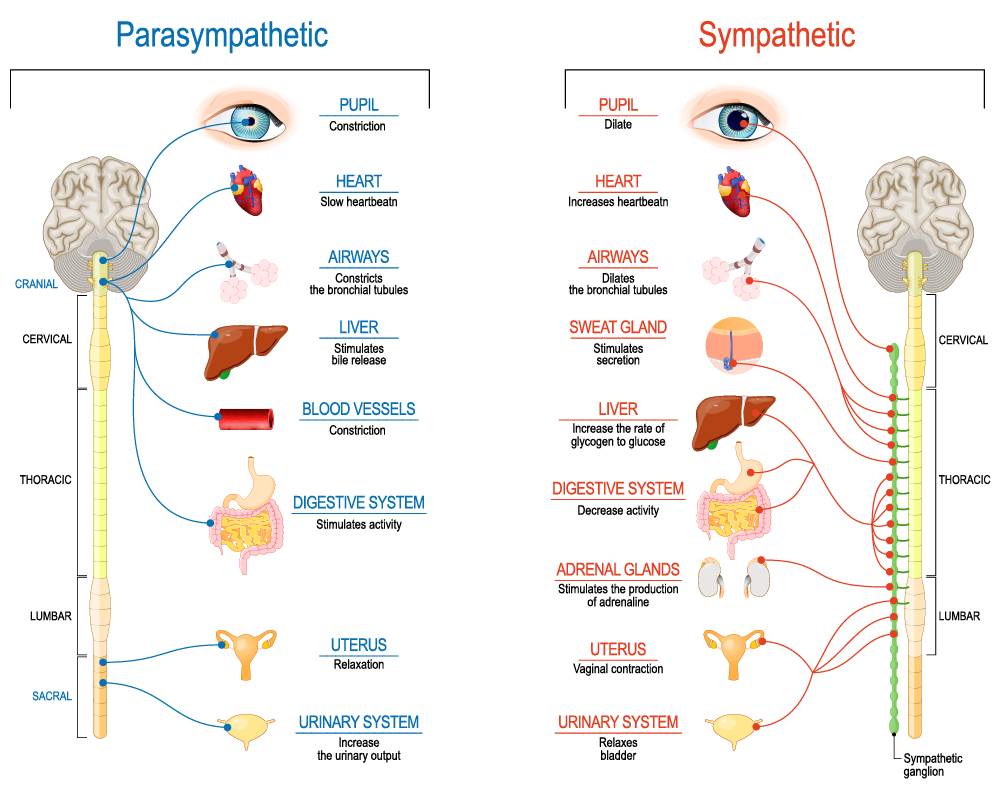

We have not written much about the vagus nerve in these pages in the past. The vagal—also called the 10th cranial nerve—is the longest and most complex nerve of the autonomic nervous system, and it has all kinds of differently functioning fibers: sensory, motor, and sympathetic as well as parasympathetic fibers. Stimulation of the vagus, therefore, leads to a large variety of generally positive effects on health, from decreasing stress and anxiety, improving digestive issues, enhancing sleep, and—yes—as in recent years has come into increasing focus, immunological effects, among those it reduces inflammation in the body.1

Here is a little bit of what, for a change, traditional Chinese medicine teaches us about this very important nerve (see Figure below):

And, importantly, we can really activate the nerve ourselves by doing the following:

Deep/slow belly breath

“OM” Chanting

Cold water face or whole-body immersion after exercise

Filling the mouth with saliva and submerging your tongue to trigger a hyper-relaxing vagal response.

Loud gargling with water

Loud singing

You may want to try one or more of those!

Reference

Dolgin E. Science 2025;:594

What does the age at menarche have to do with inflammation?

And here is something surprising: In a nationally representative sample of adult women (without diabetes) U.S. investigators recently reported in the JCEM that earlier age at menarche is associated with unfavorable inflammatory (and glucose) metabolic biomarker profiles, and these findings were especially pronounced among non-smokers.

Specifically, earlier menarcheal age was associated with higher CRP levels (P=0.006), fasting glucose, fasting insulin, and ferritin. The authors interpreted the data to mean that glucose intolerance with early menarche may be an inflammatory process. A quite sensible interpretation of their data with—of course—considerable clinical relevance!

Reference

1. Santos et al., J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2025;110:1365-1374

What does the immune system have to do with ovarian physiology?

On first impression, one may wonder why this question is even raised. But with improving understanding of our immune system and of ovarian physiology, the question has become increasingly relevant, and Belgian investigators now attempted to summarize some of those data in a Review article in Human Reproduction.1

Overall, progress has been slow, indeed somewhat embarrassingly slow in comparison to other organs in the body. Unfortunately, the authors apparently did not have much of an immunology background, as their understanding of immunological facts at times appeared surprisingly weak. One example was the false claim in the manuscript that autoimmune oophoritis can be the consequence of immune system activation against various ovarian antigens. After decades of searching, only one such antigen has been identified, and even that antigen causes autoimmune oophoritis only in women with Addison’s disease (i.e., therefore it is exceedingly rare).

They also appeared confused when defining primary ovarian insufficiency (POI). Noting correctly that ESHRE defines POI as oligo-amenorrhea for at least 4 months with FSH over 25.0 mIU/mL, close to what the CHR and much of the U.S. call premature ovarian aging (POA). In the U.S., POI stands for amenorrhea of at least six months, FSH >40.0mIU/mL, and before age 40.

It is universally accepted that POA, as well as POI (under U.S. and European definitions is associated with an increased prevalence of autoimmune findings upon testing as well as autoimmune diseases. While the authors got this association right, to claim that the incredibly rare autoimmune polyglandular syndromes type 1 and 2(APS-1 and 2) are the most frequently associated autoimmune conditions is almost ridiculous.

It is also quite remarkable that, in allegedly trying to summarize new data that link ovaries with the immune system, no mention is made of the fact that adrenals and ovaries stem from the same embryological primordium. That fact, alone, in an evolutionary model, therefore, links ovaries and adrenals where corticosteroids are produced, which, of course, play a very significant role in controlling the immune system.

Unfortunately, the whole article reads like a medical student thesis rather than a scientific article in a major medical journal. However—in fairness—it does present a small number of relevant recent discoveries.

Reference

1. Cacciottola et al., Hum Reprod 2025;40(1):12-22