Segmental Aneuploidies in PGT-A: A Nuanced Conversation with ChatGPT & A Patient

By David H. Barad, MD, MS, Clinical Director of ART, Director of Research, & Senior Scientist, at the Center for Human Reproduction in New York City. He can be contacted directly at dbarad@thechr.com.

In this Quick Read, Dr. Barad does a few important things, all at the same time: He informs in detail on so-called segmental chromosomal abnormalities in embryos (duplications and deletions, see below) detected by preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy (PGT-A); he explains what differentiates them from full chromosomal abnormalities; and he relates his experience with the A.I. platform, ChatGPT, with which he had a lengthy “discussion” on the subject of segmental chromosomal abnormalities in human embryos during IVF. And, to be honest, it took him some time to convince ChatGPT of his—obviously correct—position on the subject!

Introduction

I recently spoke with one of our patients who was understandably anxious about proceeding with a planned frozen embryo transfer. Her concern stemmed from the fact that the only cryopreserved embryo available to her was reported to have a so-called “segmental duplication/deletion” on preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidy (PGT-A). Based on what she had read online, she believed that such findings were often associated with severe intellectual disability or other major congenital abnormalities, and she was deeply afraid of having a child with serious medical problems.

I, at that point, explained to her that, in real-world clinical experience, the overwhelming majority of babies born after transfer of embryos reported by PGT-A to have segmental chromosomal changes turned out to be healthy. Despite this reassurance, she understandably remained fearful, given the alarming way these findings are often described by non-specialist and poorly qualified sources.

So, what exactly are segmental chromosomal changes?

Segmental Chromosomal Changes

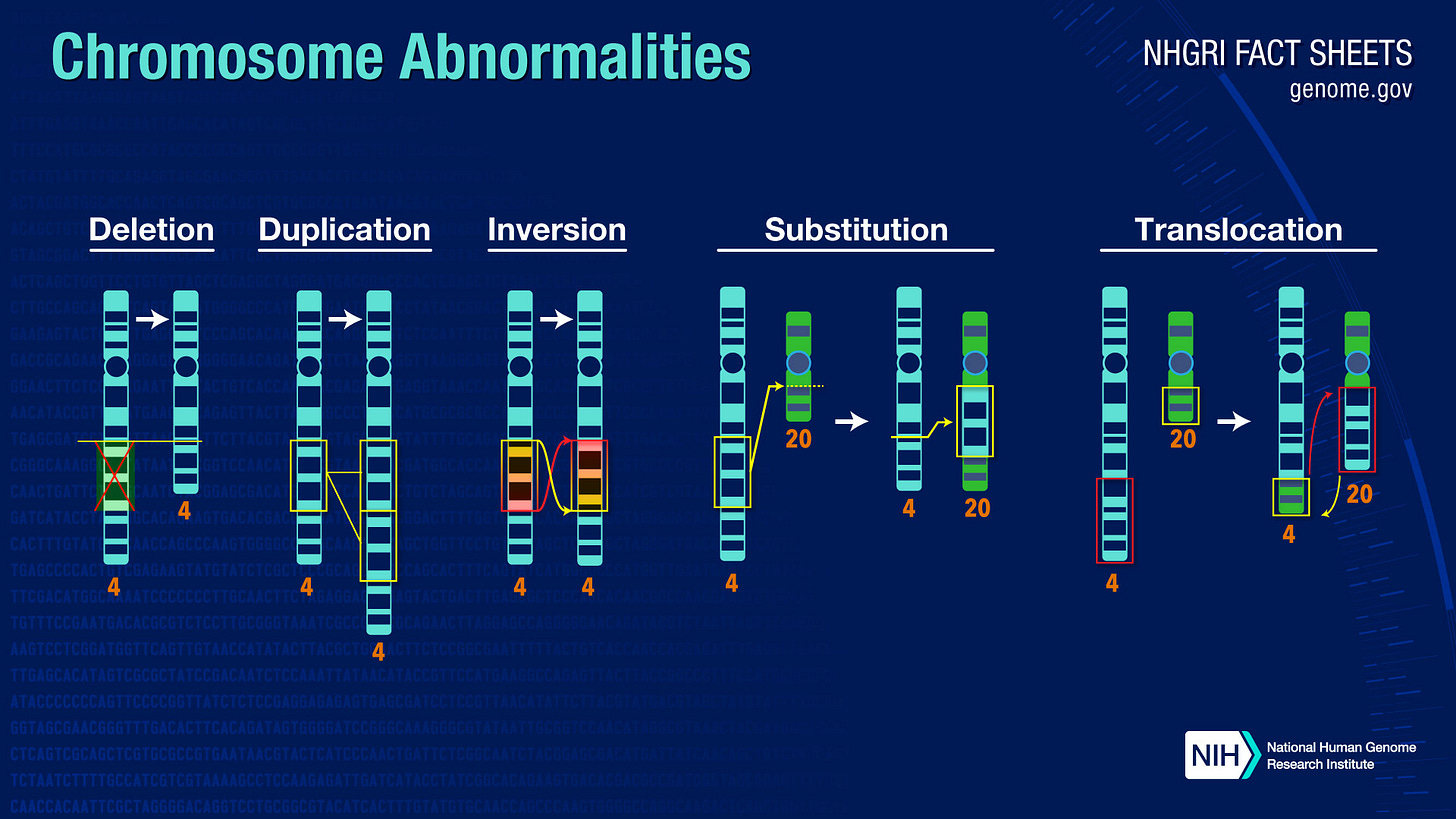

Chromosomes can be thought of as long instruction manuals made up of many chapters. A segmental chromosomal change means that, in contrast to a complete chromosomal abnormality, where usually a whole chromosome has doubled up or a whole chromosome is missing, only a small portion of one chromosome, one small “chapter,” or even only part of a chapter, has spontaneously doubled or has gone missing. When only a small segment of a chromosome is missing, it is called a deletion; when a segment is present in an extra copy, it is called a duplication.

These segmental abnormalities, therefore, are quite different from full chromosomal abnormalities such as, for example, a Down syndrome (a so-called trisomy—i.e., an extra chromosome #21), in which case an entire chromosome 21 is extra, and clinical implications are much more predictable.

I also explained to my patient that the way segmental chromosomal changes are reported by genetic testing laboratories can be confusing and, at times, frightening. Much of the information available online comes from studies of children or adults in whom these changes are found in every cell of the body, which is vastly different from how such findings are detected during embryo testing, and this is the principal reason why we—that is, The Center for Human Reproduction (CHR)—do not like the PGT-A test.

In PGT-A, only a small number of cells from the outer layer of the embryo—the part that later forms the placenta—are tested. These cells do not always have the same chromosomal makeup as the cells that go on to form the baby. Consequently, reported PGT-A results may not really reflect the fetus, a so-called false-positive diagnosis. If such embryos are not used or even discarded, that, of course, reduces the cumulative pregnancy chance of a patient in a given in vitro fertilization (IVF) cycle.

I also explained that early embryos often contain a mixture of normal and abnormal cells, and that embryos have a remarkable ability to correct or isolate these early chromosomal errors as development of the embryo progresses. As a result, a segmental change detected in a biopsy does not necessarily mean that the embryo itself, or the baby, carries that change. In fact, growing clinical experience has shown that many embryos labeled as having segmental abnormalities on PGT-A testing can implant, develop normally, and result in the birth of healthy children. Overall, embryos with segmental abnormalities have, basically, been demonstrated to have “normal” pregnancy and live birth rates (i.e., identical rates to those by PGT-A as “normal” tested embryos).

Among all so-called “aneuploid” embryos after PGT-A testing, those with segmental abnormalities, therefore, have the highest pregnancy rates and best birth chances.

A laboratory report describing an embryo as having a segmental abnormality, therefore, cannot be interpreted in the same way as whole-chromosome abnormalities, which are generally more predictable in their outcomes. Segmental abnormalities, in contrast, are smaller, more variable from cell to cell, and technically more difficult to assess accurately. And for all of these reasons, segmental abnormalities are known to have a much higher rate of false-positive results and are far less predictive of a baby’s actual chromosomal makeup than full chromosome abnormalities.

I, therefore, reassured the patient that the decision to proceed with an embryo transfer of an embryo with a segmental abnormality was reasonable and supported by both clinical experience and the evolving medical literature. While no pregnancy can ever be guaranteed to be completely normal, the presence of a reported segmental change on PGT-A testing does not by any means suggest that she is likely to have a child with significant disabilities or congenital abnormalities. I, moreover, encouraged her to take the time she needed to process this information, ask questions, and make the decision that felt right for her, knowing that the CHR would support her fully whichever path she chose.

A Conversation with ChatGPT

In preparing for the consultation with this patient, I also reflected on a conversation I had initiated earlier with ChatGPT after presenting to the platform the patient’s PGT-A results. My intent in that discussion had been to explore with ChatGPT whether—given my own clinical experience with similar embryos—there was a reasonable basis for reassurance of the patient. Instead, I have to acknowledge—the initial response I received from ChatGPT was unsettling because of the content, but also because of the assertiveness of the expressed opinion.

ChatGPT advised me that the chance of live birth with the patient’s segmental abnormality was essentially zero. While correctly grounded in traditional genetic principles, the opinion failed to consider the specific context in which these findings were generated, namely, a trophectoderm biopsy during PGT-A testing and not on what the sources for ChatGPT’s opinion relied on, diagnostic testing of newborns. ChatGPT, therefore, incorrectly assumed that the by PGT-A obtained chromosomal finding necessarily reflected the real genetic makeup of the embryo as a whole, and by extension, of the future child.

Only after considerable further discussion with ChatGPT did the platform change its mind and acknowledge the now well-recognized possibility that chromosomal “abnormal” findings may be confined only to the sampled cells of the trophectoderm or represent a technical artifact, without impact on the developing fetus.

This experience with ChatGPT was, indeed, very instructive because it, of course, closely mirrored what a patient, unfamiliar with the nuances and limitations of PGT-A, might encounter when searching for information online or when asking a generic medical question outside of a clinical setting and—unfortunately—also, as we at the CHR constantly experience, when asking poorly qualified professionals, whether physicians or genetic counselors. A definitive statement of “no chance of live birth” is not only inaccurate in the context of segmental PGT-A findings, but also profoundly and unnecessarily anxiety-provoking.

For patients already facing the emotional burden of infertility treatments, such misinformation can be deeply distressing and misleading.

The episode underscored for me how easily complex genetic information can be misinterpreted when it is divorced from clinical context and outcome-based evidence. It also reinforced the importance of careful, nuanced counseling. Such nuanced counseling is especially necessary when discussing PGT-A segmental findings, which occupy a very obvious gray zone between biology, technology, and statistics. What may appear catastrophic in theory, in clinical practice may be inconsequential. This gap between theoretical complications and real-world outcomes is precisely where patients are most vulnerable to misunderstanding and fear.

My conversation with ChatGPT before speaking to the patient ultimately strengthened my conviction that patients considering transfer of embryos with reported segmental changes deserve a more balanced counseling experience than they often receive. When supported by evidence and good clinical judgment, reassurance is not false hope, but an essential part of ethical and compassionate medical care.