What Lab-Built Implantation Models and Aging Ovaries Reveal About Fertility

Will Newly Developed Models of Embryo Implantation Finally Allow for a Better Understanding of Implantation?

Several laboratories have recently reported workable models for human implantation, raising expectations for a better understanding of the process. One, by Chinese investigators, is still at the preprint stage at eLife.¹ A second one by European investigators was just published in its full beauty in Cell.²

The first paper claims to have established an endometrial organoid culture system that mimics the window of implantation. Considering that nobody really exactly knows when this alleged implantation window starts and ends in a cycle, it seems to us that the claim of having an endometrial organoid system mimicking the window of implantation may be a little exaggerated.

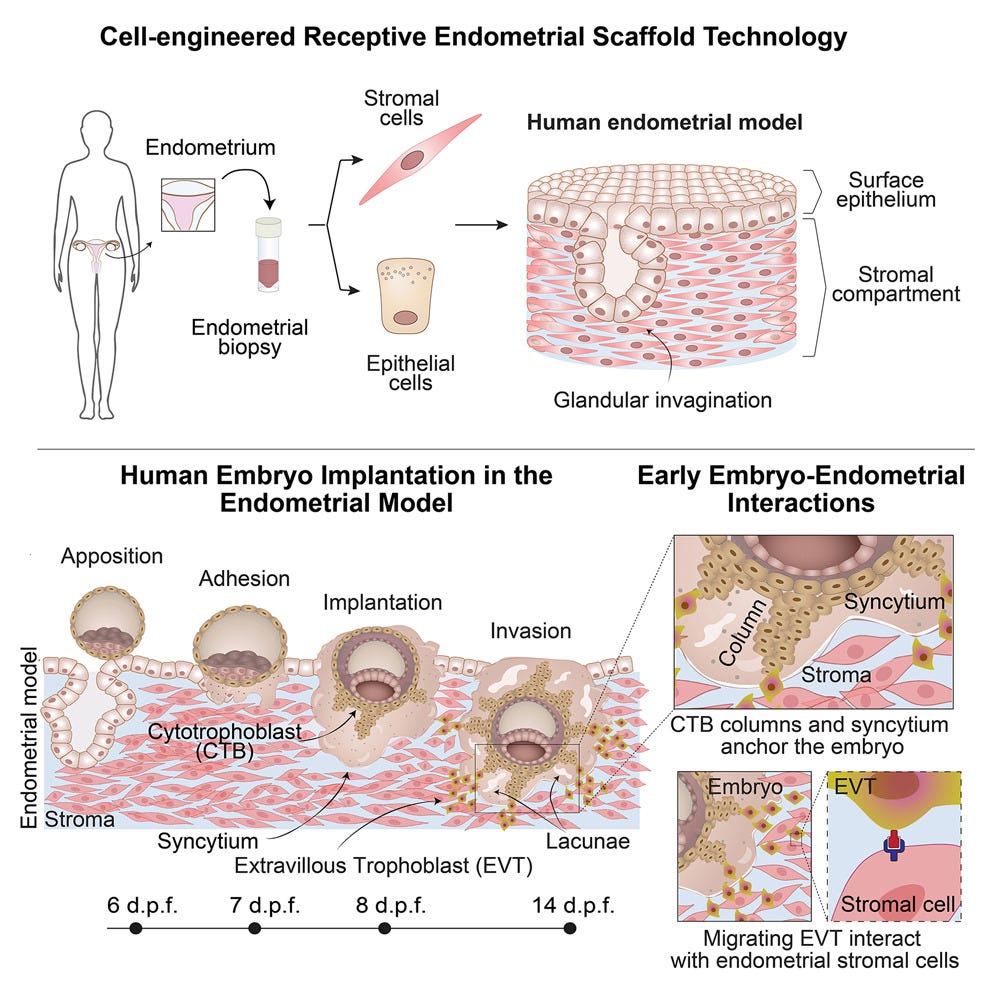

The second paper by a European collaborative established a 3D in vitro model that supposedly “supports” human implantation and development. This model of a “receptive” endometrium (what is meant by that is again a kind of implantation window but molecularly defined), with what a “receptive” endometrium is, once again, remains controversial.

Implantation of a human embryo into the endometrium is, of course, likely the most crucial event in pregnancy. It, after all, marks the very beginning of a pregnancy. It is also—for a variety of known and probably even more unknown reasons—prone to high failure rates. Even at peak fertility in the early 20s, only 1/3 of embryos will implant. By age 45, this ratio is probably around 1/20.

This European model is alleged to recapitulate the luminal, glandular, and stromal compartments of the superficial layer of receptive human endometrium. Human embryos as well as blastoids were allegedly implanted into the endometrial model, achieving post-implantation hallmarks including advanced trophoblast structures that underlie early events in placental development.

Single-cell RNA sequencing of the embryo-endometrial interface at day 14 uncovered predicted molecular interactions between conceptus and endometrium. Disrupting signaling interactions between extravillous trophoblast and endometrial stromal cells caused defects in trophoblast outgrowth, demonstrating the importance of crosstalk processes to sustain embryogenesis (see the graphic abstract below). A potentially important development in our understanding of implantation.

But there is a “but,” and it is a subject that on several occasions before has been addressed in these pages, and that is the question whether pregnancy should primarily be viewed as an endocrine event (i.e., dependent on a hormonal “window of implantation”) or an immune event, first and foremost dependent on the development of appropriate maternal tolerance toward the fetal semi-allograft (and increasingly full allograft if egg donation or a gestational carrier are involved).

We here, of course, will not rekindle this discussion; but, while not ignoring the relevance of hormones for the establishment of successful implantation and pregnancy, the CHR sees pregnancy, for biological reasons, as primarily an immune-mediated rather than endocrine condition. And this opinion, of course, also translates into clinical practice, which—for decades—has given close attention to our patients’ immune systems.

We therefore strongly believe that all the modeling of implantation will remain unsatisfactory until and unless models also receive an “immune system.”

References

Zhang et al. eLife. 2025. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.90729.3

Molè et al. Cell. 2026;189:1–19

Comparing Human and Mouse Ovaries Across Advancing Ages

Though mouse models have been used in ovarian research for decades, neither women nor men are mice. We here at the CHR learned this a long time ago, even though it was mouse work by colleagues maintaining a mouse laboratory, which finally explained to us (and whoever was interested in knowing in the world) why androgen supplementation (in our case with DHEA) in hypo-androgenic women often improves outcomes in IVF cycles.¹ Considering how difficult in vivohuman research can be—especially in the fertility field—without animal data, we still might not know why we are successfully treating women with DHEA.

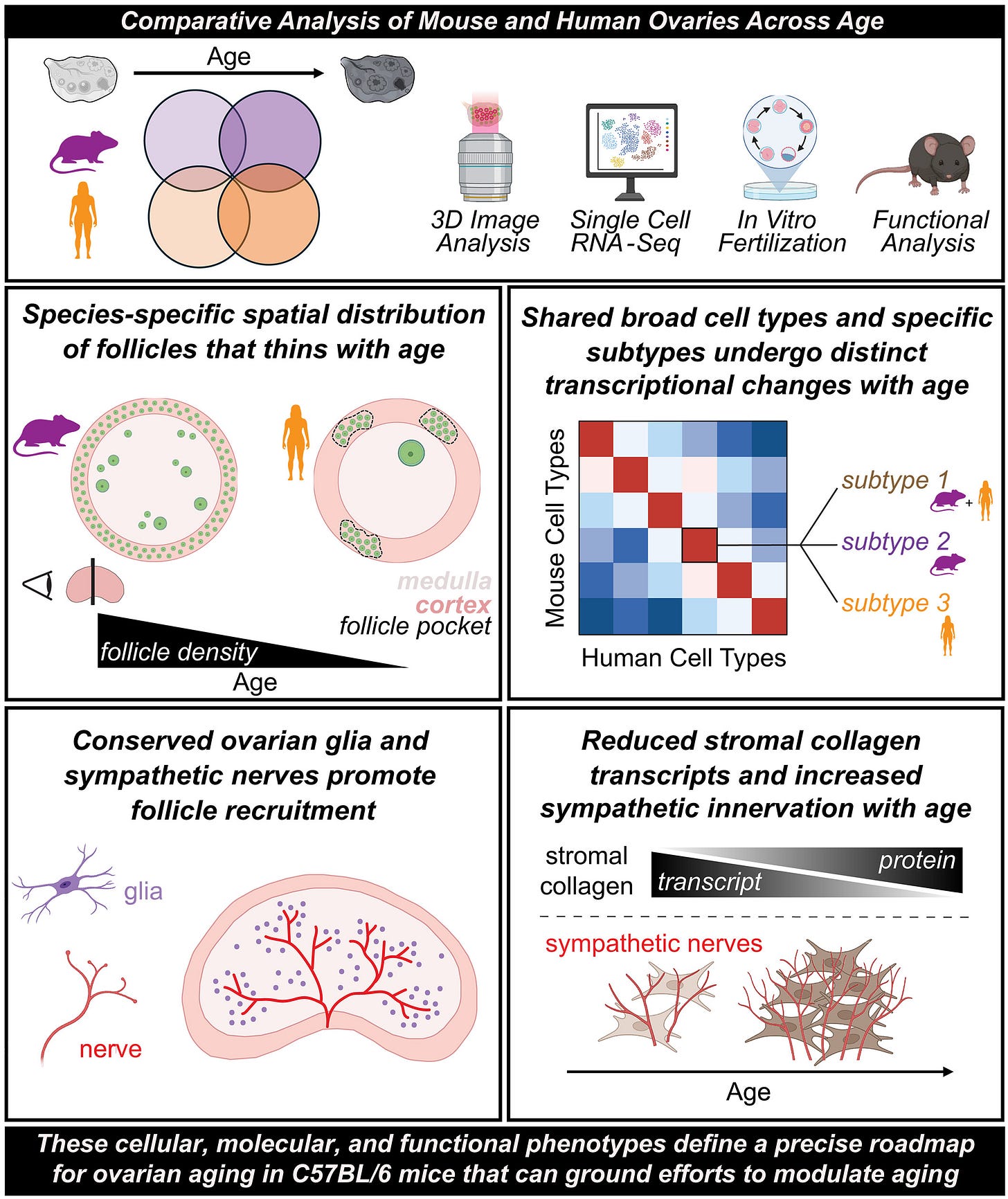

But because neither women nor men are mice, not everything observed in mice will also end up applying to the human experience. We therefore were intrigued when colleagues from UCSF recently published a paper in Science comparing mouse and human ovaries over advancing ages (see graphic abstract above).² Specifically, the authors compared ovaries between the two species using three-dimensional imaging, single-cell transcriptomics, and functional studies.

In mice, they recorded declining follicle numbers and oocyte competence during aging. In human ovaries, they studied cortical follicle pockets and decreases in density. Without going into detail, the study revealed probably more similarity than expected in the form of conserved cellular specialization. That included sympathetic nerves and glia, as well as species-specific dynamics of follicle depletion with age, oocyte maturation, and stromal remodeling.

References

Sen A, Hammes SR. Mol Endocrinol. 2010;24(7):1393–1403.

Gaylord et al. Science. 2025;390(6778). doi:10.1126/science.adx0659