When Diagnosis Outpaces Disease: An Ethical Problem

By Chloe Haack, BS, a writer and editor at the CHRVOICE and The Reproductive Times. She can be contacted at chaack@thechr.com.

Introduction

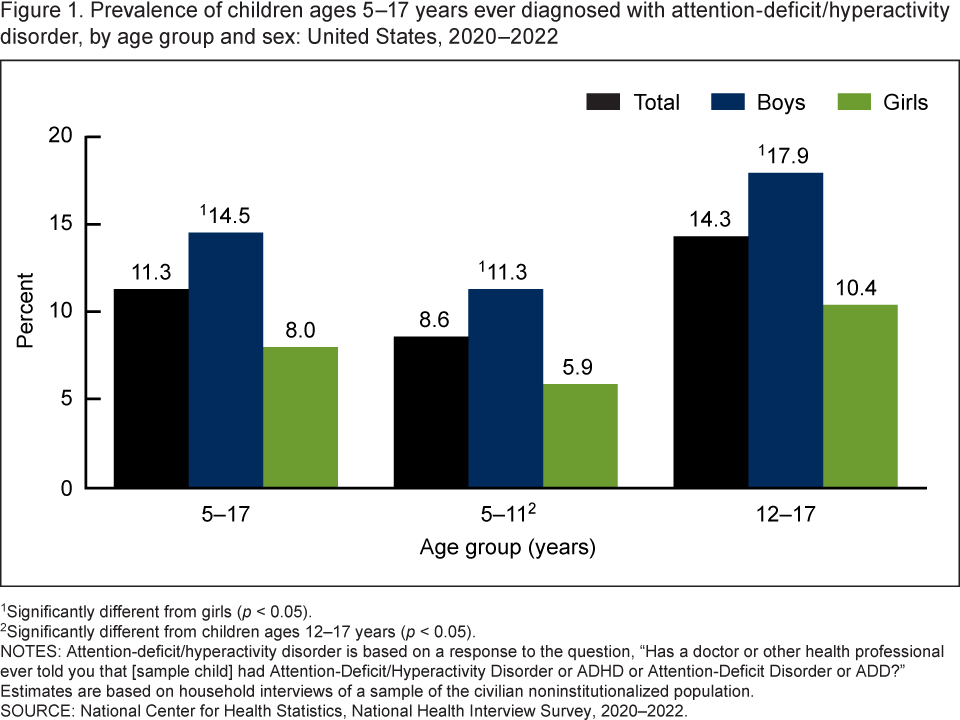

In November 2025, Nature published an article by Helen Pearson examining the rapid rise in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) diagnoses across multiple countries.¹ The explanations are familiar to clinicians: improved recognition, expanded access to care, and long-overdue diagnosis in women and adults. These developments are often framed as unequivocal progress—and in many cases, they are.

But Pearson’s reporting also makes clear that a substantial portion of rising prevalence reflects changes in diagnostic practice rather than changes in disease biology.¹ That distinction is not semantic. It is ethical. And it places responsibility squarely with physicians.

Diagnosis Is a Clinical Judgment, Not a Biological Fact

Physicians are trained to experience diagnosis as discovery—something revealed through history, examination, and testing. In practice, diagnosis involves judgment about where to draw the line between normal variation and disease.²

ADHD illustrates this clearly. Its defining features—difficulty sustaining attention, emotional reactivity, impulsivity—exist on a spectrum shared by the general population. Where that spectrum becomes pathology is not dictated by biology alone, but by clinical judgment.³

In contemporary practice, adult ADHD is often diagnosed via inference rather than demonstration: childhood symptoms reconstructed from memory, brief evaluations substituting for sustained observation, and impairment treated as self-evident rather than empirically shown.¹˒³ Individually, these decisions are defensible. Collectively, they soften the boundaries of diagnosis, and prevalence rises accordingly—not because ADHD has suddenly increased at the population level, but because medicine has grown more permissive in naming it.⁴

The ethical question for physicians centers on whether expanding diagnostic boundaries ultimately serves patients’ interests overall.

Overdiagnosis as a Professional Responsibility

Medical ethicists have been explicit: overdiagnosis reflects a clinical ethics problem in which diagnostic practice outpaces evidence of patient benefit.⁵

Colleagues at the University of Sydney in Australia define overdiagnosis as the identification of conditions that meet accepted diagnostic criteria but do not reliably improve patient outcomes, and may introduce harm through labeling, unnecessary intervention, or changes in self-concept.⁵ Importantly, overdiagnosis can occur despite appropriate clinical judgment and guideline-concordant care. From an ethical standpoint, the concern is not diagnostic error, but the absence of proportional benefit following diagnosis.

In ADHD, diagnosis frequently leads directly to pharmacologic treatment. For many patients, stimulant therapy is life-changing. For others, benefits are marginal, while harms—side effects, dependency risk, or medicalization of identity—are real.⁶ Ethical concern arises when diagnosis is treated as inherently beneficial, despite limited evidence that it reliably improves patient outcomes.

Reproductive Medicine Faces a Parallel Ethical Challenge

Consider diminished ovarian reserve (DOR). A low anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) level is commonly translated into a formal diagnosis, including in patients who ovulate regularly and have no documented infertility. Once applied, the diagnosis often shifts clinical momentum toward earlier and more aggressive intervention.⁷ At the same time, the evidence remains consistent: AMH predicts response to ovarian stimulation far more reliably than it predicts natural fertility.⁸ In practice, the diagnosis changes patient behavior more predictably than it improves outcomes.

Or consider implantation failure. In routine clinical practice, patients with two or three unsuccessful embryo transfers—outcomes well within expected statistical variability—are frequently classified as having an implantation disorder.⁹ Once this label is applied, further evaluation and intervention commonly follow, including immune testing, endometrial biopsies, and protocol modification. Outcomes that may reflect chance are reinterpreted as disease.

As in ADHD, the expansion of diagnostic categories in reproductive medicine increases prevalence not by uncovering new diseases, but by redefining clinical thresholds. In these settings, diagnosis shifts the focus from explanation to intervention.

Prevalence Is Partly Physician-Made

What ADHD and fertility medicine share is a reality physicians rarely articulate: prevalence is partly created by clinical practice.²˒⁴

When diagnostic thresholds soften, testing becomes routine, and normal biological variation is reclassified as disease, prevalence rises—even in the absence of any change in underlying disease burden.⁴˒¹⁰ Bjørn Hofmann, a Norwegian medical ethics researcher, has described this pattern as medicine diagnosing conditions that are “too mild, too early, or too much,” cautioning that such expansion strains core ethical commitments to beneficence and non-maleficence.¹⁰˒¹¹

Once diagnostic labels are applied, they often influence clinical decisions beyond what the evidence alone would support.

Diagnosis Is Not Ethically Neutral

Diagnosis alters how patients see themselves, how they make decisions, and how clinicians proceed. It introduces urgency. It reshapes identity. It creates downstream interventions.

Once a diagnosis is applied, an individual patient becomes part of a broader diagnostic category, and care may begin to follow the logic of the label rather than the specifics of the person. These dynamics unfold in a clinical context shaped by intense patient anxiety, time pressure, and a desire—shared by physicians and patients alike—for clarity and action.

From an ethical perspective, diagnosis itself is an intervention.⁵ Physicians, therefore, carry responsibility not only for diagnostic accuracy, but for diagnostic proportionality:

Does the diagnosis meaningfully improve patient outcomes?

Are downstream interventions evidence-based?

Have uncertainty and limitations been communicated honestly?

In ADHD, this entails judging when functional impairment rises to the level of clinical intervention. In fertility medicine, it requires clarity about what diagnostic tests can and cannot predict, and honesty about when urgency reflects perception rather than physiology.

Diagnostic Humility as Ethical Practice

Ethical medicine asks physicians to consider not just whether a diagnosis is correct, but whether it advances patient care. This requires diagnostic humility—an awareness of how medicine defines normality, paired with restraint in applying that authority.

The rise in ADHD diagnoses documented by Nature is not a warning against awareness. It is a reminder that physicians participate in creating prevalence through everyday clinical decisions.¹

A physician’s ethical responsibility, therefore, extends beyond diagnostic accuracy. While accuracy guards against misdiagnosis, diagnostic judgment determines whether labeling improves patient care. Because diagnosis carries lasting clinical consequences, it demands restraint as well as precision.

References

Pearson H. Why ADHD diagnoses are rising—and what it means. Nature. Published November 27, 2025.

Rosenberg CE. The tyranny of diagnosis: specific entities and individual experience. Milbank Q. 2002;80(2):237–260.

Polanczyk GV, Willcutt EG, Salum GA, Kieling C, Rohde LA. ADHD prevalence estimates across three decades: an updated systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43(2):434–442. doi:10.1093/ije/dyt261

Bruchmüller K, Margraf J, Schneider S. Is ADHD diagnosed in accord with diagnostic criteria? Overdiagnosis and the influence of client gender on diagnosis. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2012;80(1):128–138.

Carter SM, Rogers W, Heath I, Degeling C, Doust J, Barratt A. The challenge of overdiagnosis begins with its definition. J Med Ethics. 2015;41(3):264–268. doi:10.1136/medethics-2014-102220

Storebø OJ, et al. Methylphenidate for children and adolescents with ADHD. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(11):CD009885.

Tal R, Seifer DB. Ovarian reserve testing: a user’s guide. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;217(2):129–140.

Steiner AZ, et al. Antimüllerian hormone and pregnancy outcomes in women with unexplained infertility. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(4):840–847.

Gleicher N, Barad DH. Unexplained infertility and implantation failure: Is more testing always better? Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2020;18:67.

Hofmann B. Too much, too mild, too early: diagnosing the excessive expansion of disease. Int J Gen Med.2021;14:703–713. doi:10.2147/IJGM.S288593

Welch HG, Schwartz LM, Woloshin S. Overdiagnosed: Making People Sick in the Pursuit of Health. Boston, MA: Beacon Press; 2011.